Earlier this week, we ran a Q&A with Heritage experts Ed Haislmaier and Andrew Kloster about the King v. Burwell case, which was heard by the Supreme Court Wednesday:

What is the King v. Burwell case about?

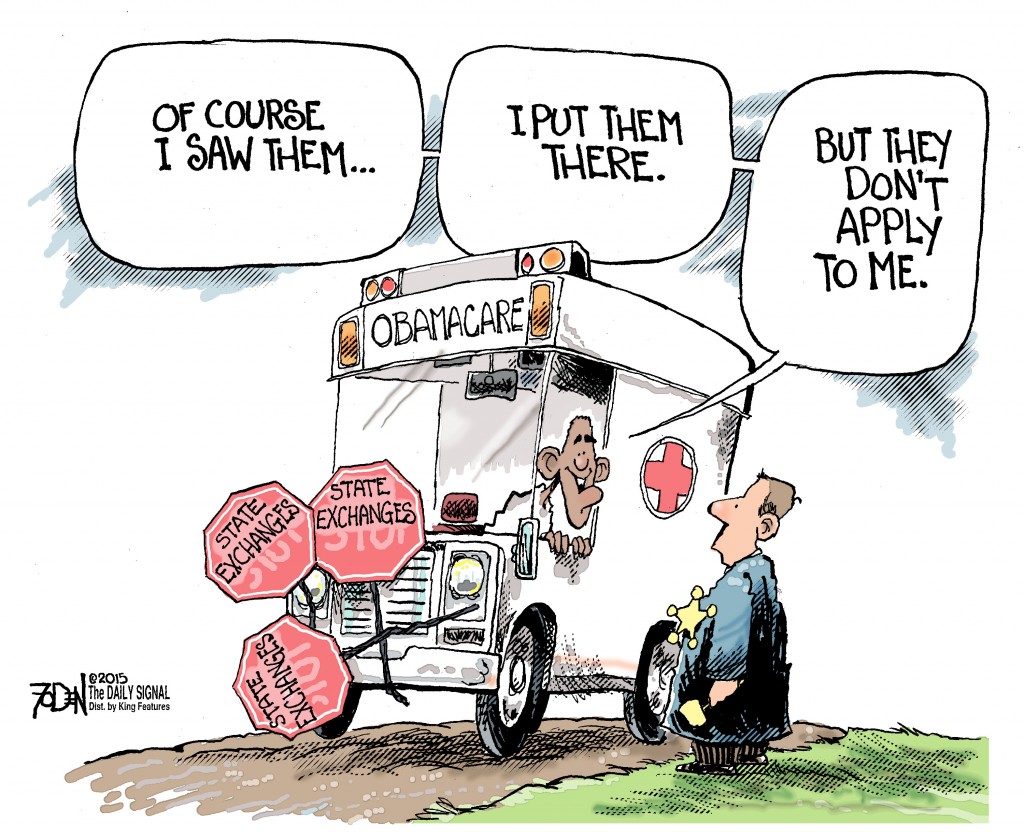

The question before the Supreme Court is whether the Obama administration overstepped its authority in issuing an IRS ruling that conflicts with the Obamacare statute. The statute allows payment of Obamacare subsidies only to individuals who obtain coverage “through an Exchange established by [a] State.”

However, the IRS rule allows subsidies to flow to individuals who get coverage through a federally established exchange as well. This interpretation was made after it became clear that many states were unlikely to set up their own exchanges because of the cost and complexity involved.

The federal government set up an exchange for the states that did not create their own—eventually 34 states—and distributed subsidies to individuals participating in them, even though the Obamacare statute seemingly did not authorize subsidies in such cases.

Who are the plaintiffs and what are they objecting to?

The plaintiffs are residents of Virginia who object to Obamacare’s individual mandate. Without a subsidy, their income levels would allow them to qualify for an “affordability” exemption from the mandate because the cost of coverage would likely be more than 8 percent of their income.

But because Virginia is a state that declined to set up a state exchange, the federal government has done so, and the administration’s regulation extending subsidies to individuals buying coverage through the federal exchange has the effect of reducing their cost of coverage relative to their incomes to the point that the “affordability” exemption no longer applies. Hence, the plaintiffs must either purchase coverage (and pay any portion of the premium that exceeds the subsidy) or pay a fine, both of which they object to.

What are the direct effects of a ruling if the Court strikes down the administration’s regulation?

The U.S. Treasury would be barred from paying Obamacare subsidies to individuals who live in states that have not established their own exchanges. There are currently 34 states that have not established their own exchanges.

How many people are likely to be directly affected by the ruling?

The most realistic estimate is that, in 2015, roughly 5.5 million people in the 34 states in which the federal government operates the exchange are expected to receive Obamacare subsidies for insurance purchased through the federal exchange. The subsidies compensate in part the effect of Obamacare increasing the cost of coverage. Thus, any dislocation is yet another in a longer list of harmful effects of the law.

Are there any indirect effects of such a ruling against the administration, and what are they?

Individuals in any of the 34 affected states whose financial circumstances are similar to those of the plaintiffs in this case might also qualify for an “affordability” exemption from the individual mandate because their unsubsidized cost of coverage would likely be more than 8 percent of their incomes.

Virtually all employers in states without their own exchanges would effectively be exempt from the employer mandate. That is because the statute specifies that an employee obtaining Obamacare subsidies through an exchange is the trigger for enforcement of the employer mandate. In the event that the Supreme Court rules against the administration, this trigger would be removed.

What should be done if the Court rules against the administration?

Congress should exempt individuals, employers and insurance plans in states that do not have a state exchange from Obamacare’s costly rules, regulations and mandates. The exemption should include items such as Obamacare’s rating rules and benefits mandates, as well as formally exempting residents of the affected states from the individual and employer mandates. Exempting affected individuals from provisions in Obamacare that increased health insurance premiums would enable those individuals to obtain more affordable coverage. As a result, it would at least partially—and possibly in some cases, entirely—offset the financial effects of losing subsidies.

In anticipation of such congressional efforts, states should pass legislation that would ensure a smooth transition from Obamacare-mandated coverage back to coverage regulated by the states. States should take the opportunity to review and assess their pre-Obamacare rules and regulations to make them as market-based and patient-centered as possible.

What should be avoided?

Congress should avoid perpetuating the complex and costly subsidies in Obamacare. The design of the subsidies creates major financial incentive for millions of Americans to shift to plans that qualify for the new subsidies; it involves additional rules, restrictions, and penalties; and is administratively complicated.

States should not pursue efforts to adopt a state exchange. States gain no meaningful flexibility from administering the exchanges in lieu of the federal government, and their long-term costs would fall squarely on the states, since any state implementing a state exchange must develop its own revenue source to fund the exchange’s annual operations.