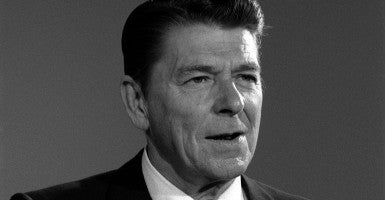

As someone who has studied and written about Ronald Reagan for more than four decades, I thought I knew the 40th president pretty well.

But a new book, “Reagan Remembered”, edited by former Amb. Gilbert A. Robinson, offers the personal and in many cases never before revealed recollections of 80 individuals, high and low, who worked in the Reagan administration.

Starting with Edwin A. Meese III, counselor to the president in the first term and U.S. attorney general in the second. These alumni confirm what a remarkable leader Reagan was—always focused on the big picture.

Meese reminds us of Reagan’s primary achievements: revitalizing the economy, rebuilding the nation’s defenses so that the Free World could win the Cold War, and reviving the spirit of the American people.

In answer to the question, “How was one man able to accomplish so much?” Meese points to Reagan’s clarity of vision and his ability to get the most out of his cabinet-style governing.

He recalls that a jar of jelly beans always sat in the middle of the Cabinet table. Whenever the discussions over a controversial issue became too intense, the president would reach over, select a jelly bean, and pass the jar around the table. This invariably cooled tempers and restored “calmer reflection.”

Often described as the most powerful man in the world, Reagan was amazingly modest. Vice President George H. W. Bush remembers his visit to the Washington hospital after the 1981 attempted assassination of the president.

Ushered into his room, Bush saw that Reagan wasn’t in his bed and looked around. A familiar voice said “Hello, George” and the vice president turned to find Reagan on his hands and knees in the bathroom. “Are you all right, Mr. President?” Bush asked. A smiling Reagan explained that he had spilled some water on the floor and was wiping it up. “I don’t want the nurses to have to mop it up,” he said. “I’m enough of a nuisance to them as it is. Be with you in a second.” Bush writes, “That’s the sort of man Ronald Reagan was.”

Reagan being a man of his word was established again when he agreed to meet with German Chancellor Helmut Kohl at the cemetery in Bitburg. It was then discovered that members of the Nazi SS were buried at Bitburg, causing Nobel Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel, among others, to demand a change in venue.

Secretary of State George Shultz tried to shift the meeting, but Kohl insisted on Bitburg. Having made a commitment, Reagan went to Bitburg, despite withering criticism by the media and the political opposition. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher subsequently told Shultz that “no other leader in the free world would have taken such a political beating at home in order to keep his word.”

For Reagan, politics was a means, not an end. In 1976 when he was locked in a tight battle with President Gerald Ford for the Republican presidential nomination, his Texas campaign manager arranged for Reagan to speak in the largest church in Houston. To his great surprise, Reagan turned down the opportunity.

The Texan argued that “thousands of conservative voters will see you and millions more will read about it. The venue couldn’t be more prestigious.” Reagan quietly replied, “I’m a very religious person, but I don’t wear it on my sleeve. And I never want to use religion for political purposes.” The event never took place.

Since his film acting days, when he helped stop the attempted communist takeover of the Hollywood trade unions, Reagan was an implacable anti-communist. In November 1978, he visited Berlin for the first time and stood before the infamous Berlin Wall.

His national security adviser Richard Allen recalls that suddenly Reagan’s hands clenched and his jaw set and he said in a low almost growling tone, “We’ve got to find a way to knock this thing down!” Less than a decade later, he again stood before the Berlin Wall and declared, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” Two years later, the Wall came tumbling down and communism collapsed in Eastern and Central Europe.

He believed in doing the right thing and not caring who knew that he did it. Campaigning in North Carolina in 1976, he agreed to meet with a small group of blind children but without any reporters or cameras present. He talked with the children for a moment and then asked if they would like “to touch my face to get an idea of what I look like?”

Campaign aide and future presidential speechwriter Dana Rohrabacher remembers “these eight kids putting their fingers on his face. When they were finished they all had big hugs—and then we were off to the next stop.” Rohrabacher says, “Any candidate running for president I’ve ever met would give a million dollars to have a picture like that.” Not Ronald Reagan.

He was as quick-witted as anyone who ever occupied the White House. In 1983, in the course of a deep White House discussion about proposals to “freeze” the building of nuclear weapons, someone brought up the suggestion made by several U.S. senators—a “build-down” rather than a freeze.

“How would that work?” the president asked. For every new modernized nuclear weapon the U.S. built, it was explained, we would retire two so that in time we would have many fewer weapons. “Well,” said the president without hesitation, “I have a proposal. For every senator they elect, let’s retire two.”

Secure in his own skin, he delighted in making fun of those who criticized him. His gubernatorial secretary Helene von Damm, who would later serve as U.S. ambassador to Switzerland, remembers that during the Vietnam protests, a bunch of hippies camped outside the state capitol in Sacramento. They carried a sign that said, “Make love, not war.” Gov. Reagan smiled and said, “I got a look at them and I am not sure they are capable of either.”

President Reagan knew his Constitution. Once, recalls special adviser Edward Rowny, when cabinet members were complaining that the president was spending too much on defense, he responded firmly: “As president of the United States my most important duty is to defend the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic. If we lose our freedom, all is lost. Through a policy of peace through strength, everything is possible.”

Summing up the essential qualities of Reagan, Meese quotes British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery: “Leadership is the capacity and will to rally men and women to a common purpose and the character which inspires confidence.” The recollections of the 80 men and women in “Reagan Remembered” attest that Reagan was such a leader and possessed that kind of character.