The Drug Enforcement Agency created a fake Facebook profile of a woman and used the account to message drug dealers—all without her knowledge or consent.

Now, after facing a media firestorm and a lawsuit, the federal government will settle with the woman for $134,000.

It all began in 2010 when the DEA arrested Sondra Arquiett for the possession of cocaine with the intent to distribute it. To obtain a reduced sentence, she pled guilty and cooperated with the government by allowing them to search her phone for evidence.

The DEA, however, did far more than simply look through Arquiett’s phone for her contacts. DEA decided to impersonate Arquiett on social media to lure other members of the drug ring into contacting her.

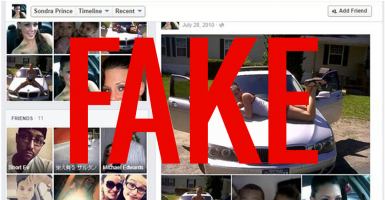

DEA Special Agent Timothy Sinnigen used pictures of Arquiett stored on her cellphone to create a fake Facebook profile. The profile included a photograph of Arquiett holding her two young children, and a suggestive photo of her lying on the hood of a car with the caption, “At least I still have this car!”

After being told by a friend about the suspicious account with her name on it, Arquiett sued the DEA. According to her complaint, she “suffered fear and great emotional distress because, by posing as her on Facebook, Sinnigen had created the appearance that she was willfully cooperating in his investigation of the narcotics trafficking ring,” which placed her life in danger.

In response to the complaint, the Department of Justice argued that, by pleading guilty and agreeing to cooperate, Arquiett had given implied consent for the officers to access and use information stored on her phone to aid ongoing criminal investigations.

But that defense is laughable. Allowing the government to search your cellphone is not tantamount to allowing the government to create a false public image of who you are or to agreeing to take life-threatening risks on the government’s behalf.

The government’s claim certainly was not enough for Facebook, Inc., which noted that creating phony profiles violates its terms of service agreement, or for the media, which rightly criticized the decision to impersonate someone without her consent.

After months of negotiation, the government decided to settle.

“This settlement demonstrates that the government is mindful of its obligation to ensure the rights of third parties are not infringed upon in the course of its efforts to bring those who commit federal crimes to justice,” Richard Hartunian, the U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of New York, said in a statement.

But perhaps what is most telling from the settlement agreement is that government did not admit any wrongdoing. Instead, it stands by its untenable argument that Arquiett impliedly consented to use the evidence found in her phone to assist law enforcement activities in any imaginable—and unimaginable—way. Moreover, the settlement does not specifically prohibit the DEA from using similar undercover tactics in the future.

That is unfortunate. Law enforcement officers frequently use social media to aid in their criminal investigations by posing as members of a drug ring in order to make contact with other crew members. But that is not what happened here.

“I may allow someone to come into my home and search but that doesn’t mean they can take the photos from my coffee table and post them online,” observed University of Pennsylvania law professor Anita Allen.

If someone consents to a search, then it should be expected that the government will view private information which they would not have had access to without your permission. What they find can be shared among law enforcement agencies, introduced as evidence during trial, and shown to opposing counsel and witnesses.

But consent to a search does not allow the government to use what they find to create a false identity of your likeness, post it on Internet social media, and make contact with drug dealers in an attempt to make an arrest.

The U.S. Supreme Court has squarely held that the police may not invite the media along on the execution of a search warrant so that the events can be broadcast on network TV. Doing so, the Court held would violate the privacy rights of the owner or occupant of the space being searched.

There is no material difference between what the DEA did in this case and what the Supreme Court expressly held that law enforcement officers cannot do. Both would violate the privacy rights of the person subjected to the search, in this case Arquiett’s rights.

DEA Special Agent Sinnigen should have known that.