Since Fidel Castro seized power in 1959, a steady stream of Cuban refugees has taken to the waves in a desperate attempt to escape the Communist regime.

For more than 50 years, refugees have braved the 90-mile, shark-infested stretch of water between Cuba and Florida. In search of freedom, they set sail in flotillas of rickety fishing boats, ingeniously converted cars, and crude homemade rafts.

For her part, the United States welcomed each successive wave with mostly open arms until President Clinton amended the 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act in 1994. Since then, only Cuban refugees who make it to dry ground have been granted political asylum.

As Washington renews diplomatic relations with Havana, The Daily Signal takes a look back at the historic Cuban exodus to freedom.

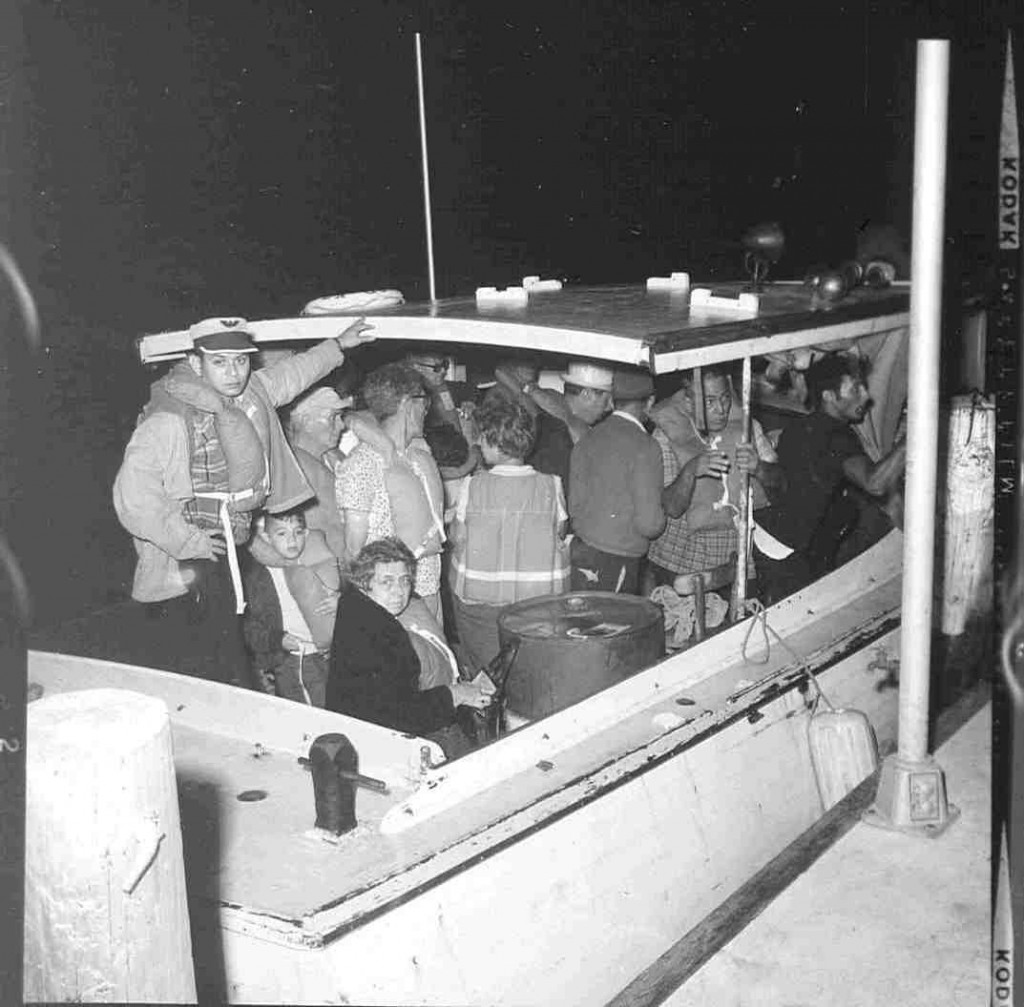

In October 1965, Castro announced that the port of Camarioca would be opened for any Cubans wishing to sail for the “Yankee Paradise.” More than 2,900 fled before Castro closed the port.

In a converted fishing boat, a Cuban family waits to set sail for Florida. (Photo: U.S. Coast Guard Camarioca Boatlift Collection)

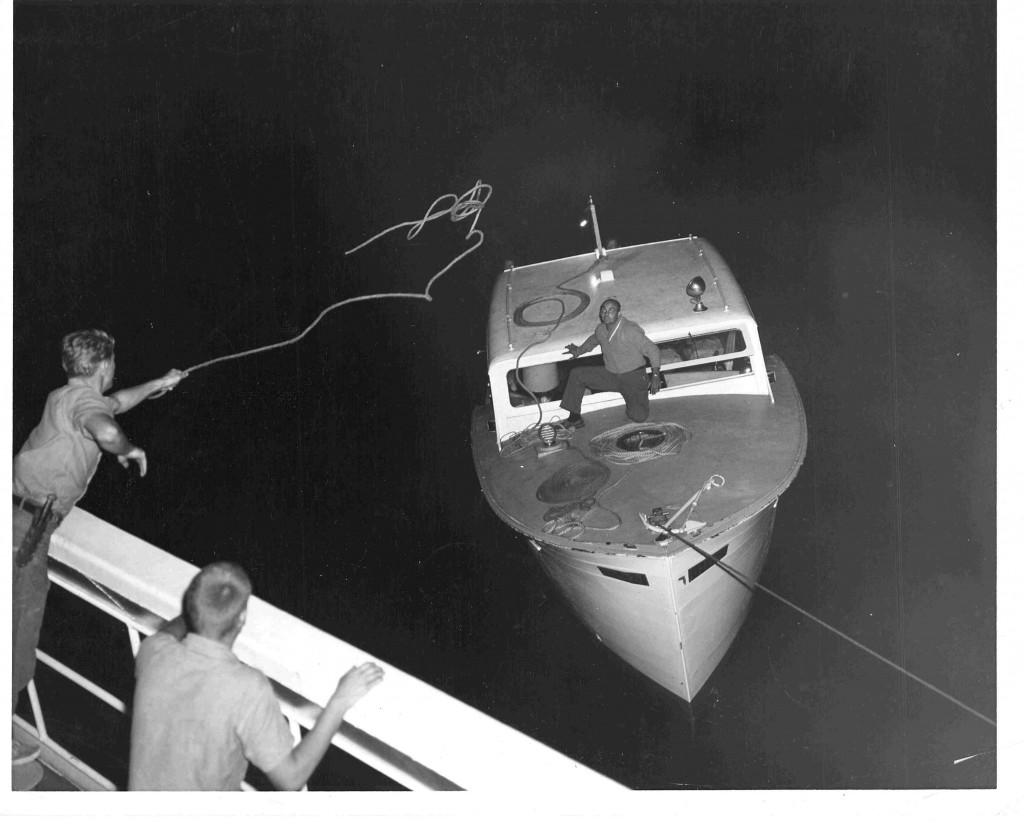

The U.S. Coast Guard answers the distress signal of a Cuban speed boat and tows it to the Keys in November 1965. (Photo: U.S. Coast Guard Camarioca Boatlift Collection)

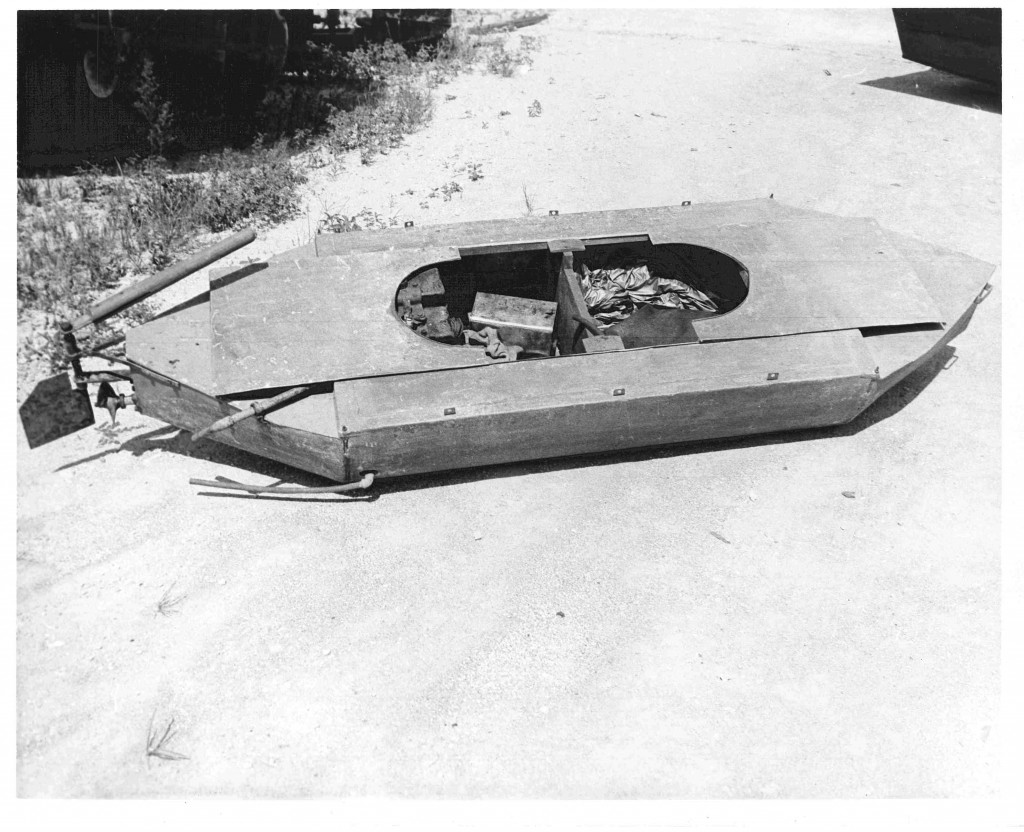

Cubans set sail in whatever possible. One ingenious refugee made it to freedom with this homemade kayak powered by a lawnmower engine. (Photo: U.S. Coast Guard Camarioca Boatlift Collection)

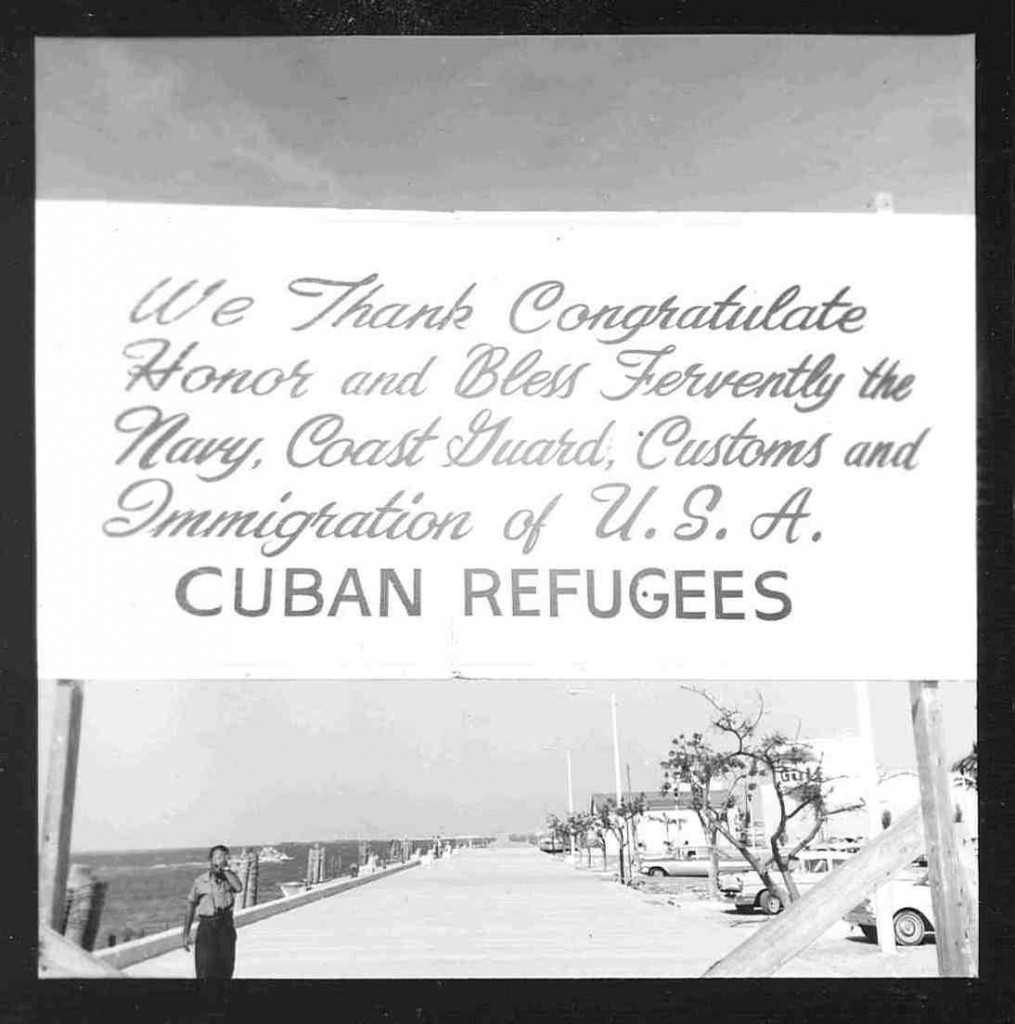

In 1965, the United States welcomed refugees with open arms, sending the Navy and Coast Guard to their rescue. In this photo, Cuban refugees show their thanks. (Photo: U.S. Coast Guard Camarioca Boatlift Collection)

In 1980, facing intense political pressure, Castro opened the Mariel port for those wishing to leave. More than 125,000 left the island.

One of thousands of American yachts unloads Cuban refugees in the Florida Keys before returning to pick up more. (Photo: Florida Keys Public Library/CC By 2.0)

Discarded refugee boats piled up on a Miami pier by the Coast Guard in May 1980. (Photo: Florida Keys Public Library, Raymond Blazevic/CC By 2.0)

An American refugee receiving center for Cuban exiles in May 1980. (Photo: Florida Keys Public Library, Raymond Blazevic/CC By 2.0)

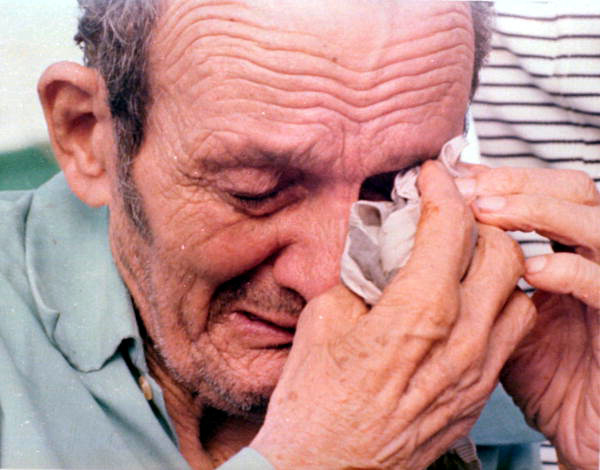

A Cuban refugee cries upon arrival in Florida Keys in 1980 (Florida State Library and Archives, Dale McDonald/CC By 2.0)

With the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, economic conditions in Cuba suffered dramatically and thousands of immigrants took flight.

A Cuban raft lists to one side as Coast Guard officials come aboard to rescue refugees. (Photo: U.S. Coast Guard Historian Office/CC By 2.0)

The Coast Guard saved so many refugees that the discarded craft were marked “USCG” to notify helicopters that all had been safely rescued, August 1994. (Photo: U.S. Coast Guard Historian Office/CC By 2.0)

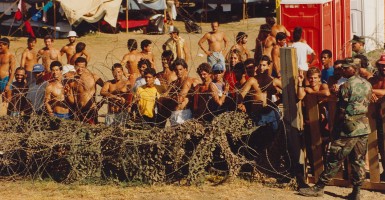

The U.S. rescued so many Cuban refugees it became necessary to return them to the Naval Base at Guantanamo Bay before shuttling them to the States. (Photo: U.S. Coast Guard Historian Office/ CC By 2.0)

Memorial at Guantanamo thanking “American friends” 1995. (Photo: Duke University, Elizabeth Campisi/CC By 2.0)

Struggling to manage the flow of refugees, President Bill Clinton amended the 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act. The subsequent “wet foot/dry foot” policy allowed refugees to remain only if they reached dry land. If detained at sea by the Coast Guard, refugees must return to Cuba.

Modern rafters make their way to Miami in 2008. (Photo: U.S. Coast Guard 7th District, Miami/ CC By 2.0)

Smugglers charge hefty fees to outrun Coast Guard patrols. Sometimes they made it. Sometimes they didn’t, as was the case in this 2002 photo. (Photo: U.S. Coast Guard)