“Planes, Trains and Automobiles” is not just the name of Steve Martin and John Candy’s 1987 everything-goes-wrong comedy film. It’s also the prospective casualty list of the foundation-led anti-fossil-fuel campaign called the Divest-Invest movement.

The new crusade “responds to climate change by urging universities, churches, pension funds and other big institutional investors” to destroy petroleum and coal companies by dumping their shares and reinvesting in a “fossil-free clean-energy economy,” modeled loosely on the anti-apartheid activism of the 1980s.

In the past two years, dozens of public and private institutions have announced plans to divest fossil fuels from their portfolios. In August, a Bloomberg New Energy Finance white paper quoted one executive as saying Divest-Invest is “one of the fastest-moving debates I think I’ve seen in my 30 years in markets.”

The debate made headlines at the U.N. Climate Summit in September, where the “Divest-Invest Global Movement” delivered divestment pledges from 50 “philanthropic” foundations and more than 700 participating institutions and individuals” worth more than $50 billion.

At the United Nations, a small, functional “secretariat” was created to “survey all existing and pending Divest-Invest commitments, vetted by a committee of movement leaders.” That gave a patina of legitimacy to a “grassroots-driven movement” that was actually a “foundation grant-driven movement.”

Does all this hype matter? It could.

Even though there’s scant chance the movement can purge the nearly $5 trillion in oil and gas equities, the Bloomberg analysts think that “coal divestment could be relatively easy,” with existing shares worth less than 5 percent of oil and gas equities and large institutional investors much less invested in coal.

And an Oxford University “Stranded Assets” study asked, “What does divestment mean for the valuation of fossil fuel assets?” It found that dumping stocks may not even be necessary to destroy the oil and gas industry because “stigmatizing” can do it.

“[T]he stigmatization process, which the fossil fuel divestment campaign has now triggered, poses the most far-reaching threat to fossil fuel companies and the vast energy value chain. Any direct impacts pale in comparison.”

Why is that?

“In almost every divestment campaign we reviewed from adult services to Darfur, from tobacco to South Africa, divestment campaigns were successful in lobbying for restrictive legislation affecting stigmatized firms.”

Regulatory bans could be fatal.

The unanswered questions

Stigmatizers behave as if fossil-free alternatives are available for everything. Are they?

What if somebody answers the unasked question and reveals transportation’s vulnerability to stigmatization and government restrictions? The stock market is an open door that investors can enter and exit at will, and sometimes shocking news leads to shocking selloffs. If the Oxford researchers are right, stigmatization and restrictions could bring down the oil and gas industry in a jolting overnight panic.

What if the fossil fuel supply chain does suddenly vanish for lack of capital? What then?

What shall we do with America’s 254.4 million registered fossil-fueled passenger vehicles? Junk them? Convert them to biofuels or electric batteries or hydrogen? Force everyone to buy new? Where is the biomass or power grid or fueling network for that stupendous new load? Or do we just ban cars and forget being a mobile culture?

How will we power America’s 26.4 million registered commercial trucks and the 2.4 million heavy-duty trucks that deliver more than 70 percent of all freight, including our food? Where is the fossil-free infrastructure to take over that demand? How would we react to empty food shelves in every market and hungry millions ready to do anything for a meal?

What will fuel our 39,000 merchant ships? What about the estimated 40,000 ships of other nations? Go nuclear? The technology exists, but it’s not clear that we have the uranium and shipyard capacity for some 80,000 retrofits or new builds.

How will we keep rail freight carrying our bulk cargoes? Maybe hydrogen, which emits only water when burned? Experimental test locomotives are now being fueled by massive hydrogen tank cars and pulling standard strings of freight cars. None of these Hindenburg-on-rails experiments have exploded yet.

What will we use to make plastics, lubricants, asphalt for paving roads, wax for sealing frozen food packaging, fertilizer, linoleum, perfume, insecticides, petroleum jelly, soap, vitamin capsules, pharmaceuticals and the 6,000 other petroleum products we all use?

Without transportation fuel, modern civilization would collapse into an unimaginably horrendous chaos.

How will we fuel jetliners? Jet fuel is a high-energy, freeze-resistant mixture of a large number of different hydrocarbons, and that includes emerging biofuels. The aircraft biofuel industry hopes to cut jetliner carbon dioxide emissions in half—by 2050.

Zero-emission jet fuel is not expected on any time horizon. Even the synthetic fuels under study are all hydrocarbons. A fossil-free jet fuel would have to be extremely high energy per gallon because jetliners carry all their fuel inside the wings; none is carried beneath the passenger cabin. That fuel supply must take the plane to destinations near and far.

It also has to be freeze-resistant, because the atmospheric temperature at cruising altitudes is about 50 degrees below zero Fahrenheit, and even in-wing heaters can’t keep gel-prone fuels from clogging. So, do we go fossil free and jetliner free? Anybody who recalls the closure of American airspace after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks knows what that means. U.S. stocks lost $1.4 trillion in one week.

Without transportation fuel, modern civilization would collapse into an unimaginably horrendous chaos. Don’t think it can happen? Who’s the denier now?

Who is behind Divest-Invest?

Unlike most grant-driven movements, the Divest-Invest movement is not just a blob of faceless “foundations.” It can be traced to a single private foundation, the little-known Washington-based Wallace Global Fund II—2012 assets, $115,471,213.

The WGF’s millions originally came from the 1920s-era Hi-Bred Corn Co. of Henry A. Wallace, who parlayed his wealth into political power and stints as secretary of agriculture, secretary of commerce, vice president under Franklin D. Roosevelt and presidential nominee in 1948 of the ultra-left Progressive Party.

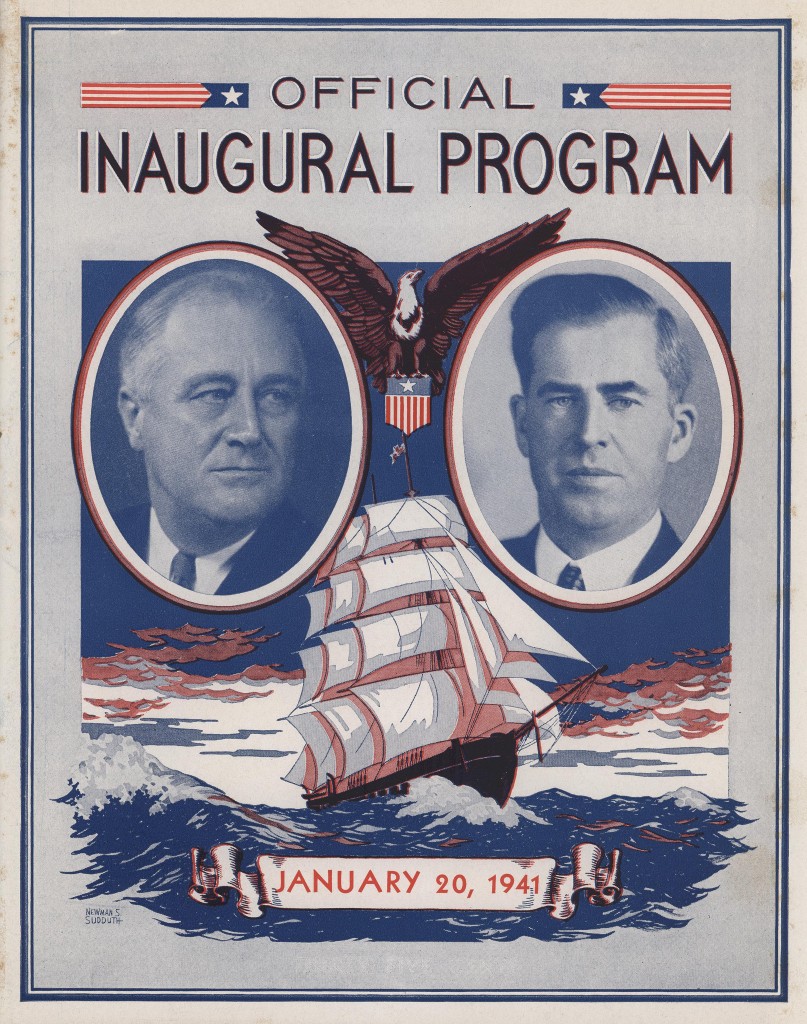

The cover of the official program of the ceremonies for the third inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt and Henry A. Wallace. (Photo: Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections)

The current heirs, co-chairmen Scott and Randall Wallace and treasurer Christy Wallace, along with executive director Ellen Dorsey (2012 compensation, $298,596), realized their investments in coal companies conflicted with their ideological goal of eliminating coal use and divested the offending securities, according to the fund’s website. It was a short step to building their example into a movement.

In June 2011, Dorsey and program manager Richard Mott (2012 compensation, $238,434) convened a group of college students and environmental activists at the fund’s offices to discuss launching a coal divestment campaign on the nation’s campuses.

According to the fund’s IRS Form 990PF reports, it gave more than 20 cooperating groups a substantial chunk of its nearly $15 million in grants in 2011 and 2012. Recipients included the Sierra Club Student Coalition, $180,000; the Hip Hop Caucus, $40,000; the anti-corporate lawsuit group As You Sow, $160,000; and Bill McKibben’s 350.org, $205,000 to front the campaign. The scope quickly expanded from coal only to all fossil fuels.

McKibben gets the credit for starting the Divest-Invest movement, largely because of his scary articles in Rolling Stone and Grist. But McKibben is the sock puppet in this fight and has secured only 13 commitments to divest, all from small colleges with small endowments. He doesn’t have traction in the trustee councils of big universities, which refuse to give any symbolic divestment pledge because they have a legal fiduciary trust to keep their institutions solvent.

Matt Dempsey of Oil Sands Fact Check, told The Daily Signal, “The divestment campaign is pure political theater designed to draw attention around fringe anti-fossil-fuel efforts leading up to the UN Climate Conference in France in 2015. No wonder leading academic voices on campuses across the country are rejecting this extreme campaign that would significantly cut student resources while doing nothing to improve the environment.”