Little more than one year after Harry Reid, the Senate’s top Democratic leader, invoked the hotly disputed “nuclear option,” the change of rules may stand after the Republicans officially take over Jan. 6.

As majority leader, Reid pushed through a change in Senate rules on advancing presidential nominations just over 14 months ago. At the time, Republicans were outraged and contended that Reid’s move would come back to haunt him.

Now, the GOP is grappling with whether to return to the old filibuster rule or keep the change.

>>> Commentary: What the New Nuclear Options Means for the Senate

That change effectively eliminated the time-honored filibuster to block a president’s nominations to the lower courts and executive offices. Under the old rules, senators could debate whether to confirm a nomination until 60 of the 100 senators voted to invoke cloture and end the debate. That is, 41 votes could bring the process to a halt.

Reid secured Senate approval, 52-48, to lower that threshold from 60 votes to a simple majority of 51. Nominations to the Supreme Court were excluded from the change.

After months of threats, the top Senate Democrat turned to the “nuclear option” after Republicans blocked President Obama’s nominations to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit and to the Federal Housing Finance Agency.

The president nominated three judges to the bench of what is called the nation’s second-most-powerful court. He selected Mel Watts, a member of Congress at the time, to head the agency that oversees Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. They were confirmed after the rules change.

Following Republicans’ sweep of Senate seats in the Nov. 4 midterm elections, GOP lawmakers began deliberating whether to return to the old rule.

>>> It’s a Wave: Republicans Take US Senate, Build Majority in House, Grab Governorships

Republicans will have 53 Senate seats in the next Congress. All GOP senators, including those newly elected, will take part in debating the future of the rule.

“I think it’s rank hypocrisy if we don’t [roll back the rule],” Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., told The Hill newspaper. “If we don’t, then disregard every bit of complaint that we made, not only after they [Democrats] did it but also during the campaign. I’m stunned that some people want to keep it.”

Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., one of McCain’s biggest allies, said returning to the 60-vote threshold to avoid a filibuster would make it more difficult for nominees to be confirmed — which he sees as a good thing — and would make nominations a “collaborative process.”

“I think it would be smart for us to go back to the way it used to be, getting the Senate back to the way it’s always been and making it harder to get people into the court and into the executive branch, not easier,” Graham told Hugh Hewitt, a conservative radio host.

Others contend that changing the threshold back to 60 votes from 51 sets a different standard for Republicans than for Democrats.

In an op-ed last month in the Wall Street Journal, Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, wrote:

To restore the rule now, after Mr. Obama has installed his controversial judges, would cement a partisan double standard: When Democrats control the White House and Senate, judicial nominations need only 50 votes; but when Republicans control both, judicial nominations require 60 votes, allowing Democratic minorities to block Republican nominations.

Ed Whelan, president of the Ethics and Public Policy Center, agrees.

“Republicans would be setting up this ridiculous asymmetry where conservative nominees need 60 votes when Republicans control the Senate, and liberal nominees only need 50 votes when Democrats control the Senate,” Whelan told The Daily Signal. “That’s not a way to improve the courts.”

>>> First Filibuster, Now Blue Slips: A New Fight over Judicial Nominations

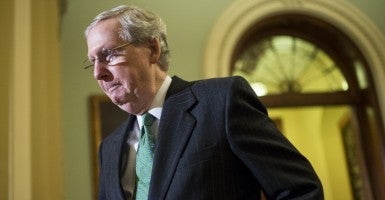

Whelan said that returning to the 60-vote threshold for judicial nominees would have little consequence in the next two years, as Obama’s nominees could be stopped both at the committee level and by incoming Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky.

However, going back to the old rule would hold more weight after 2016 — especially if a Republican wins the presidency in November. Then, Democrats would have more leverage in blocking nominations.

“I think that, for reasons I’ve argued, it’s impossible to reinstate the 60-vote threshold in a durable way,” Whelan said. “Reinstating it temporarily would just provide a huge gift for the Democratic minority if a Republican president is elected in 2016. I don’t see the sense in that.”

With the rule already changed, he also contends, it’s difficult to revert back to the 60-vote threshold.

“As some have said, the genie is out of the bottle, and it can’t be put back in.”

However, Michael Hammond, former general counsel to the Senate Steering Committee, warns that eliminating the judicial filibuster would lead to the end of the legislative filibuster.

“There is no conceptual difference between the way you destroy nomination rules by the nuclear option and the way you destroy the legislative filibuster by the nuclear option,” he wrote at RedState.com.

Hammond contended that those advocating for leaving current filibuster rules in place are “laying the groundwork for the destruction of the legislative filibuster.”

In a separate post, Hammond pointed to the 2016 presidential election and said that should a Democrat win, having a 60-vote margin to confirm judicial nominations is vital.

“If you look at the landmark cases over the past half-century, most of them are a result of bad legislation that got through,” he wrote. “The legislative process is important. The Senate is important. And relying on the courts to save you from its destruction is foolish.”

In his first six years in office, Obama nominated 305 judges to the federal bench — 252 to district courts and 53 to appeals court. He named a total of 132, more than a third, over the past few weeks.

Obama’s predecessor, George W. Bush, nominated 256 judges over his first six years. He named a total of 324 judges throughout his presidency.

Historically, invoking what today’s lawmakers call the nuclear option has been considered only on a few occasions.

In 1841, Sen. Henry Clay of Kentucky, leader of the Democratic-Republicans, threatened to use the lower threshold after a bank bill he proposed faced opposition. More than 150 years later, in the 1990s, Democrats proposed the nuclear option as a way to eliminate the filibuster.

In 2005, Republican senators threatened to invoke the option after Democrats blocked a series of Bush’s nominations.

At the time, Reid criticized Republicans for trying to “change willy-nilly a rule of the Senate.” Three years later, as majority leader, the Nevada Democrat discussed whether to use the nuclear option.

“As long as I am the leader, the answer’s no,” Reid said:

I think we should just forget that. That is a black chapter in the history of the Senate. I hope we never ever get to that again because I really do believe it will ruin our country.

>>> How Harry Reid’s Last Act as Majority Leader Directly Benefited His State