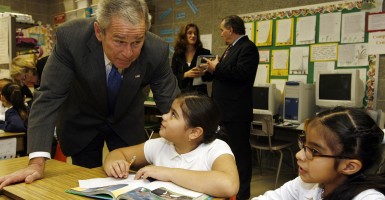

Lawmakers already are talking about reauthorizing No Child Left Behind — the George W. Bush-era education initiative. “I’d like to have the president’s signature on it before summer,” said Sen. Lamar Alexander, the Tennessee Republican who will assume chairmanship of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee when Congress convenes in January.

But lawmakers should be pursuing bold education reforms, not searching out weak legislative compromises that fail to limit federal overreach. Congressional conservatives should take this opportunity to rewrite No Child Left Behind in a way that empowers state and local educators, not Washington bureaucrats.

Previous proposals introduced by Alexander and Rep. John Kline, R-Minn., would have streamlined No Child Left Behind and created some nominal flexibility for states and school districts. But more substantive reforms are in order. The following four policy goals should accompany any reauthorization of NCLB:

First, policymakers should enable states to completely opt out of the programs that fall under No Child Left Behind. One such proposal is the Academic Partnerships Lead Us to Success Act . Including the A-PLUS approach in a prospective reauthorization of No Child Left Behind would let states consolidate their federal education funds and use them for any lawful education purpose they deem beneficial. This would allow states to escape NCLB’s prescriptive and programmatic requirements and use funds in ways that would better meet their students’ needs.

Next, policymakers should work to reduce the number of programs that fall under No Child Left Behind. The original Elementary and Secondary Education Act — the precursor to NCLB — included five titles, 32 pages and roughly $1 billion in federal funding. By the time ESEA was reauthorized for the seventh time in 2001 as No Child Left Behind, new mandates had been imposed on states and local school districts, and the law authorized dozens upon dozens of federal education programs, a reflection of national policymakers’ tendency to create a “program for every problem.”

To pay for the dozens of competitive and formula grant programs funded under NCLB, the annual cost of the federal initiative now exceeds $25 billion. The growth in program count and spending over the decades has failed to improve educational outcomes for students and, as such, should be curtailed.

Policymakers also should eliminate burdensome federal mandates. Accountability and transparency “should be vehicles to reinvigorate the relationship of the American people with their schools rather than merely mechanisms employed by government officials to oversee and hold government schools accountable,” wrote former Deputy Education Secretary Eugene Hickok and education researcher Matthew Ladner in a 2007 analysis of NCLB.

To achieve that goal, Congress should eliminate the many federal mandates within NCLB masquerading as accountability, including Adequate Yearly Progress requirements, Highly Qualified Teacher mandates and costly “maintenance of effort” rules, which require states to keep spending high in order to receive federal funding.

Finally, and at a minimum, policymakers should include a state option for Title I funding portability. The $14.5 billion Title I program accounts for the bulk of No Child Left Behind spending. It serves one of the 1965 ESEA’s original and primary purposes by channeling additional federal funding to low-income school districts.

However, Title I funds are distributed through a convoluted funding formula which, as researcher Susan Aud has noted, includes “provisions that render the final results substantially incongruent with the original legislative intention.”

To make Title I work for the disadvantaged children it was intended to help, the program’s funding formula should be simplified, and Congress should let states make the funding “portable,” allowing it to follow a child to the school of his parents’ choice — public, private, charter or virtual.

During any prospective ESEA reauthorization, Congress should reduce program count (and associated spending), eliminate federal mandates on states and local school districts and create portability of Title I funding. Such an approach represents a first small step toward reform. Bold reforms are needed, including the opportunity for states to completely exit the 600-page regulatory behemoth that is No Child Left Behind.

Originally appeared in the Washington Times.