Since 2007, the birth rate in the United States has been declining. Today, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a report on the 2013 birth rate, announcing that “the U.S. general fertility rate was at an all-time low in 2013.” Here we reprint Jonathan Last’s essay from the 2014 Index of Culture and Opportunity.

When we talk about the “total fertility rate,” we mean the average number of children that the average woman would have over the course of her childbearing years. This is not a hard number, but rather a statistic that changes with time—a historical snapshot.

Juxtaposing these snapshots, however, reveals a clear and unsettling development: For the past 10 years, America’s fertility rate has been trending downward. This is of intense interest because the fertility rate shapes the nation’s age profile, impacts the economy, puts entitlement programs at risk, and even influences foreign policy.

>>> The 2014 Index of Culture and Opportunity

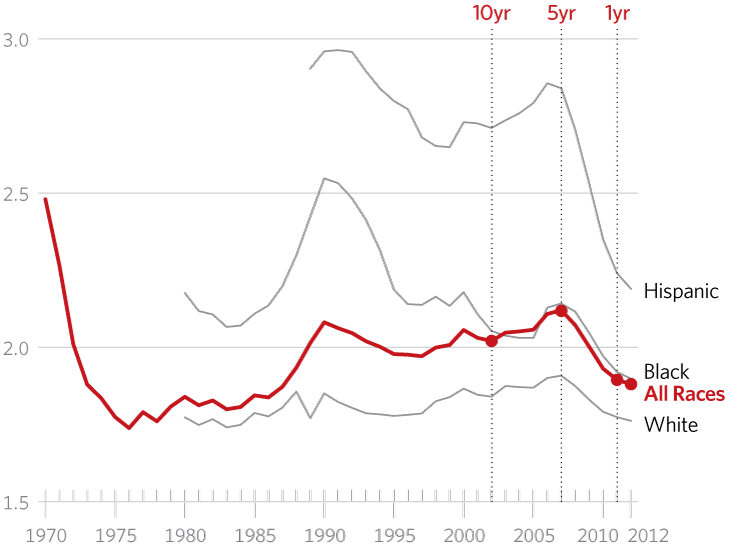

The U.S. total fertility rate first dipped beneath the replacement rate of 2.1—that is, the rate at which, absent immigration, the population remains constant—in 1972. Between then and 2012, it has reached replacement level only twice, in 2006 (when it was 2.11) and 2007 (2.12). In every other year, this rate has been sub-replacement.

Excepting those two blips, over the past 10 years, fertility in America has entered a marked decline, reaching a low of 1.88 in 2012.

The reasons for this decline are manifold, with factors ranging from culture to economics. For instance, fertility dropped steeply after 2007 as recession gripped the country and unemployment soared: Young adults and people in their prime childbearing years decided to postpone childbearing until their economic prospects improved.

The biggest contributor to this overall decline, however, is the plunge in Hispanic American fertility. Over the last 10 years (2002–2012), the fertility rates for white and black Americans have dropped by 4.3 percent and 7.5 percent, respectively. Hispanic Americans, on the other hand, have seen their fertility rate plummet by 19.2 percent.

The important question about Hispanic fertility is: Will the fertility pattern of recent immigrants continue tumbling toward the national average?

There is good reason to believe that it will. Indeed, the family structure of America’s Hispanic population is already in decline, suffering from higher rates of divorce and out-of-wedlock births, as well as a delay in age of first marriage. Should this weakening of the Hispanic American family continue, overall U.S. fertility rates would fall even further, until, within the next 10 years, they eventually mirror Europe’s low rates.

Such low fertility rates are problematic for two primary reasons. First, Europe’s low fertility rates have persisted for two generations and, as a result, the welfare state is now unsustainable. As a population continues to age, younger workers are needed to replace, and, through the welfare state, support, older retirees. However, low fertility rates have left Europe without enough younger workers, and a rapidly aging population.

Second, there is the danger that the culture’s fertility ideals will be fundamentally altered as fertility drops. In America, a high ideal fertility rate remains the cultural norm: People still want children, even if they do not have them—which means that it is still possible to find a way back to the replacement level. But once a society’s idealized fertility rate slips below replacement—as it has done in several European countries—decline is inevitable.