Finally, it is official. On Tuesday, the International Monetary Fund announced China has surpassed the United States as the world’s largest economy.

The U.S. has held the distinction since 1873, when it overtook Great Britain. Given growth trajectories of the last few decades, this should come as no surprise. Neither is it necessarily anything for Americans to worry about. It depends on how the U.S. manages the situation.

There are two basic methodologies in measuring a nation’s gross national product. Purchasing power parity, or PPP, takes into account the difference in price levels between countries (explained in detail here). The price of most items is significantly lower in China than in the U.S., but total output is now roughly the same.

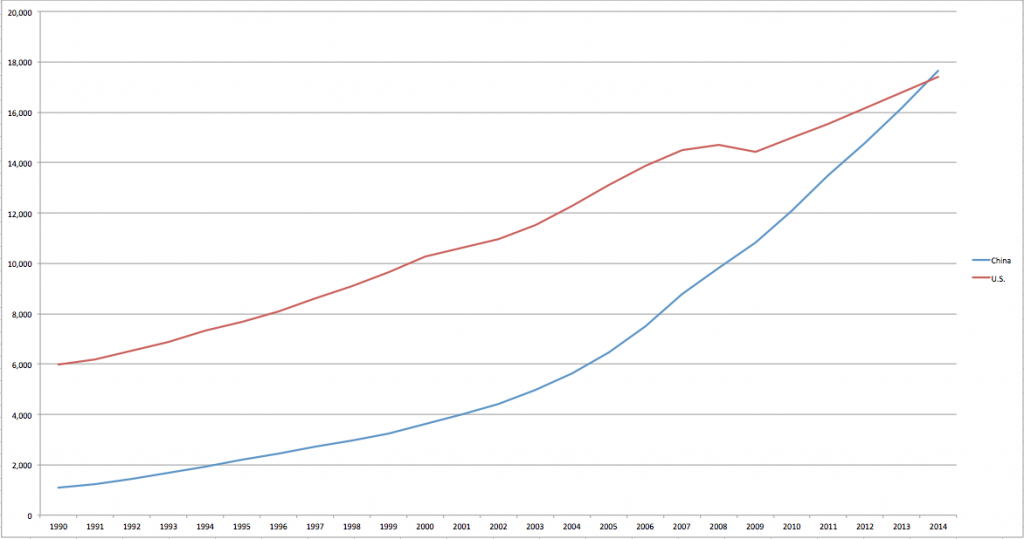

The IMF now estimates the U.S. and Chinese economies are $17.4 and $17.6 trillion respectively, as measured by PPP. As recently as 2005, the U.S. economy was approximately twice the size of China’s. In just five more years, the IMF expects China’s economy to be 20 percent larger.

The changing of the Guard (GDP millions $ PPP)

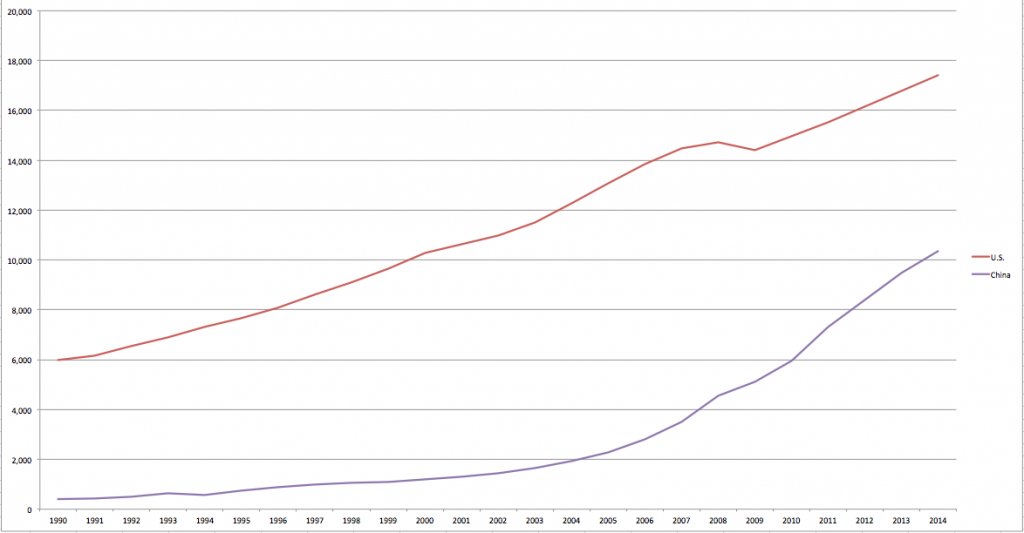

The second methodology ignores price-level differences between countries and measures output at current exchange rates. By this measure, the U.S. economy is $7 trillion larger. It will take China some time to close this gap.

Still a sizable Gap (GDP, billions $, current exchange rates)

There are advantages to size. America’s large population and massive national economy gave it the political power to help shape the post-World War II international order. China’s greater assertiveness in recent years also relates to the growth in its economy. And although there remains a great gap in per capital income—it’s $7,600 in China and $54,700 in the U.S.—China’s growth contributes both to its government’s coffers and its international influence.

That a nation with nearly four times the population of the U.S. would one day have a larger economy is neither shocking nor a threat. It is good the Chinese people have greater opportunity today than both their immediate forbearers and more distant ones. A China more open to trade and investment also is good for the world—not least American investors, exporters and consumers.

The threat arises from the power that accrues to state and party as a result of its economic performance. Managing that threat is a matter of consistent, principled American foreign policy backed by a commitment to strong national defense, and also free markets. If China’s economic performance presents a threat, it is only because the U.S. is lacking in those commitments.