Here we go again. The Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) has announced a new low-income housing proposal. The FHFA is in charge of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, two government-sponsored mortgage enterprises that played central roles in the housing market crash in 2006.

Apparently, the old policies didn’t do enough damage.

Friday’s Wall Street Journal notes that even this new plan could backfire, but the Journal doesn’t fear another credit bubble. Instead, the article bemoans a lending contraction caused by banks making only the types of loans they want to keep on their balance sheets.

In other words, banks could be less likely to make loans and sell them to Fannie Mae, a practice that had become common (in part) because it allowed banks to offload part of their financial risks to government-backed companies.

In light of the recent mortgage settlements with the Justice Department, though, it has become clear that selling loans to Fannie or Freddie is riskier than once thought. It now makes much more sense for banks to make only lower-risk loans that they are willing to hold, rather than sell to Fannie or Freddie.

Of course, several Dodd–Frank Act rules have made even that strategy more difficult.

The Journal notes that another possible outcome is that nonbank lenders will try to fill this lending “gap” by making loans to low-income families that banks won’t touch:

But that has its own risks, as nonbank lenders aren’t as tightly supervised as the banks. In fact, it was the growth of nonbank lenders that helped push the mortgage market over the edge of sanity during the last housing bubble.

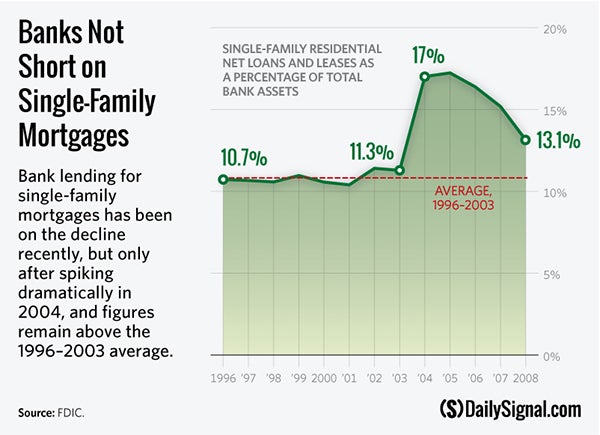

Growth in nonbank lenders certainly helped to push the market, but let’s not lose sight of the real culprit: Fannie and Freddie drove this market, even for banks. The article includes an excellent chart that shows the 2006 drop in banks’ single-family mortgage lending, but it’s missing the pre-2000 spike in lending.

Banks, in other words, increased their single-family mortgage lending right along with the nonbank lenders. From 1995 to 2003, bank lending for one-to-four-family residential mortgages hovered around 11 percent as a percentage of total assets.

This figure then shot up to more than 17 percent in 2004, and then started crashing with everything else in 2006. These figures indicate that there is no lending “gap” that needs to be filled.

Federal policies inflated a bubble and it popped. We don’t need new policies to inflate another bubble.

We need to get rid of federal policies that create credit bubbles so that we don’t have to rehash all of these arguments again in the coming decades.