Listen to the radio and you might run across a segment that sounds something like a news report. A newsy music introduction plays as a woman’s officious-sounding voice begins narrating a story. In a stilted delivery that appears to mimic that of a news anchor, the woman states, “In a move demonstrating the FBI’s valuable role of protecting national security, Director James Comey creates a separate Intelligence Branch…”

It turns out this isn’t a news report at all. And the “news anchor” is actually a public affairs specialist.

How many tax dollars are being spent for the FBI to promote itself?

You might call the radio spot a faux news report brought to you by the FBI. It’s called “FBI This Week,” produced and distributed regularly on the radio, via podcasts and on the Internet along with three other FBI productions.

Is this a much-needed public service? Or self-serving propaganda? Are the segments masquerading as independent news reports? And just how many tax dollars are being spent on the FBI’s promotional efforts?

“[T]he programs that we produce are ultimately designed to aid and assist the public in protecting itself against crime,” says Susan McKee, the FBI’s chief of investigative publicity and public affairs.

In some cases, that may be true. But it’s unclear how the Aug. 15 edition of “FBI This Week” helps us protect ourselves against crime.

Instead, it promotes FBI Director James Comey’s creation of “a separate Intelligence Branch.” Again, mimicking a news story format, it includes “interview” excerpts with the executive assistant director of the new branch, Eric Velez-Villar. He tells listeners in a comment pre-approved by the FBI for air: “As the director says, we are a national security law enforcement organization that uses, collects, and shares intelligence in everything we do.”

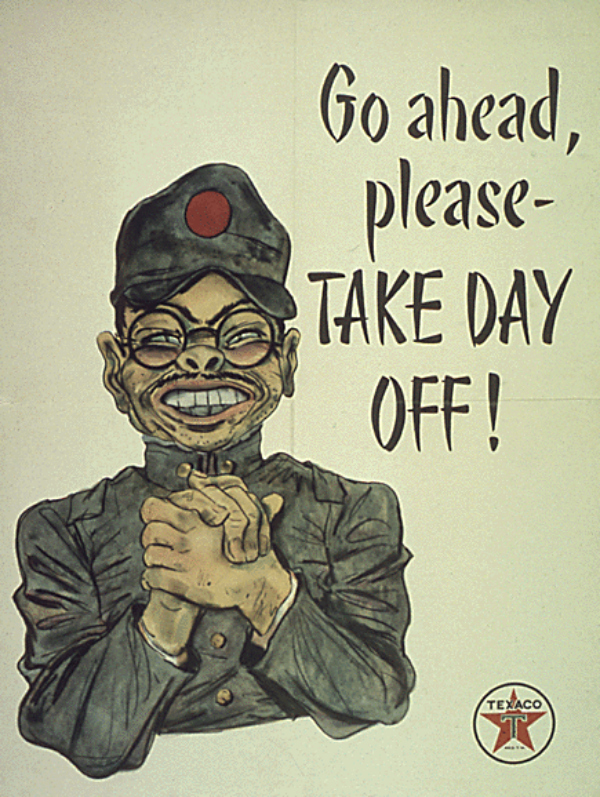

Long History of Government Information Activities

The FBI is just one of many federal agencies using tax dollars to engage in this sort of information activity: a longstanding yet growing practice.

The FBI public affairs specialist who first returned my queries on this topic is Mollie Halpern: the voice on the radio spots. When I tell her that I’m looking into federal agencies using public resources to create their own facilities and staff to self-produce information segments, she remarks, “The FBI’s been doing it longer than anybody … decades and decades and decades!”

FBI radio began in 1965, according to the FBI. The first series was called “FBI Washington” and aired on ABC. In 1990, it was reformatted and renamed “FBI This Week.” Since then, more than 1,200 one-minute spots have aired.

Any hint of the government’s engaging in what some might consider domestic propaganda efforts can be a sensitive issue.

Federal law makes it illegal for the government to engage in domestic propaganda.

The Smith-Mundt Act of 1948 authorized the U.S. government to generate and disseminate programming in foreign nations to combat widespread misinformation about U.S. policies, but it specifically forbade creation of programming for U.S. audiences. Furthermore, it directed the U.S. government to “reduce” its “information activities” where there was adequate dissemination by non-governmental means, such as an independent news media.

The law didn’t contemplate today’s dynamic in which domestic government information efforts attempt to compete with, or sometimes replace, news coverage by independent organizations.

Increasingly, federal officials are end-running reporters and taking their unfiltered messages straight to the public using public resources.

Selective Information

The irony is that at the same time government public affairs departments flood the public with information they want to disseminate, they often withhold public information requested by the public or the news media.

I asked the FBI’s McKee about the cost of producing the FBI’s various radio segments. She told me the cost is “negligible” and “handled by a public affairs specialist in addition to her other public affairs related duties.”

What is the budget for the FBI’s Office of Public Affairs? That’s where I hit a roadblock.

A 2012 photo of FBI Office of Public Affairs employees Jeff Mazanec and Susan McKee. (Photo: FBI.gov)

“I am not in a position to comment on the Office of Public Affairs’ personnel numbers or budget,” McKee told me via email.

“I don’t really need a comment on the budget,” I replied. “I just need the numbers. (Are you saying this is classified information? If not, how can I find them?)”

Three days passed with no answer, so I probed again.

McKee finally answered, “No, the number is not classified. You can find the budget numbers on-line.”

In 2007, the FBI racked up $11.9 million in public affairs expenses.

In other words, the FBI will tell you everything you didn’t want to know about Comey’s new Intelligence Branch, but it won’t cough up a basic, public budget number. I had already searched online and it wasn’t easy to find. I set off looking once again.

On my way, I found out a lot of other things about the FBI public affairs office:

- I found several postings for FBI public affairs jobs that pay salaries ranging from $56,000 to $136,000.

- I found the FBI was criticized for “wasting” tax dollars on a public affairs program that provides FBI consultants to Hollywood.

- But the best resource I found was a 2008 report from the inspector general. It says that, in 2007, the Justice Department, which oversees the FBI, employed 325 public affairs specialists at a cost of $33.1 million. (That doesn’t count expenses and personnel devoted to community outreach, responses to public solicitations of information or component museum and historian staff.) The biggest chunk of the total is attributed to the FBI which, at the time, racked up $11.9 million in public affairs expenses and employed 124 public affairs officials. That’s enough employees in the FBI’s public affairs department alone to staff the equivalent of what the government considers two “large businesses.”

Disclosure?

The Federal Trade Commission requires commercials that mimic news formats to carry conspicuous disclosures that they are, indeed, paid commercial advertising.

With public agencies in the quasi-news business, should their products also carry a disclosure to avoid the same confusion? Should they clearly tell listeners that the message is generated using their tax dollars?

Do taxpayers deserve to know the FBI is airing faux news reports?

“The only thing we’re promoting is public awareness so, no, I don’t think there is a need for a label,” the FBI’s McKee told me. “Within each program the narrator clearly identifies herself as an FBI employee and the programs are found on official FBI sites/pages.”

In fact, in the Aug. 15 story on “FBI This Week,” the narrator doesn’t clearly identify herself as an FBI employee. The segment follows a typical news format where the reporter signs off with the location of the assignment and the title of the feature. But to those who are listening closely, the positive message is the clue that there’s a government sponsor.

>>> Listen to the “Intelligence Branch” segment

“The first class of intelligence analysts to graduate from the FBI Academy since sequestration reports to duty this month,” says Halpern in the report. “From FBI Headquarters, I’m Mollie Halpern with ‘FBI This Week.’”

“FBI This Week” airs on ABC Radio as a public service on a space-available basis. This program, along with “Wanted by the FBI,” “Gotcha,” and “Inside the FBI,” is posted to FBI.gov, the FBI’s Facebook page, Twitter account and uploaded to iTunes at no cost.

This is a Daily Signal special feature.