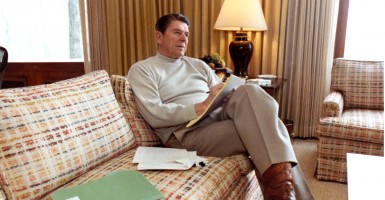

Thirty-three years ago this month, President Reagan picked up his executive signing pen and affixed his name to one of the most sweeping pieces of tax legislation in U.S. history: the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981. Rarely has any bill been more aptly named. The country had been pummeled for years at that point by the effects of “stagflation” and an economic malaise that helped defeat President Carter’s bid for a second term. The 1981 tax cut was Reagan’s bold attempt to get the economy back on track by doing something that seemed counterintuitive to many; namely, cutting taxes. More like slashing taxes, really. The top marginal individual tax rate then was a staggering 70 percent; the 1981 act cut it to 50 percent. (Follow-up legislation would cut it still further, to 28 percent.) And the cuts were across the board. The bottom rate, for example, dropped from 14 percent to 11 percent. There were many other aspects to the 1981 act: estate taxes were cut drastically, depreciation deductions were accelerated, and tax rates were indexed for inflation (beginning in 1985), among other features. Added up, they represented strong medicine – and they gave the economy just the shot in the arm it needed. Critics insisted it wouldn’t work. How, they wondered, could lowering taxes help? Jack Kemp, one of the most courageous champions of the 1981 cuts, explained the rationale: “Every time in this century we’ve lowered the tax rates across the board, on employment, on saving, investment and risk-taking in this economy, revenues went up, not down.” The strong economic recovery that followed the cuts proved Reagan and Kemp right – and helped propel the former to a landslide re-election victory in 1984. The lesson we should take from this? Reagan saw a problem and acted. Taxes were much too high 33 years ago, and they were strangling the economy. So he ignored the naysayers and did the right thing. We have a similar tax-related problem on our hands today – and it requires us to act as decisively as Reagan did. I’m talking about the problem of “corporate inversions.” Don’t let this wonky term throw you. It simply refers to the process by which a U.S. company merges with a foreign business and moves the new joint business’s headquarters to the foreign country. Pfizer and Medtronics are among the businesses that have been looking to invert. Why would they do that? Is it because they are, as President Obama and other critics have put it, unpatriotic? Hardly. It’s because the United States has the highest corporate-tax rate in the developed world, and because we’re the only country that taxes our businesses on their foreign income. That puts U.S. businesses at a serious disadvantage compared with their foreign counterparts. This fact appears lost on those who accuse these companies of dodging their responsibilities. According to Allan Sloan of Fortune, these companies benefit from “our deep financial markets, our democracy and rule of law, our military might, our intellectual and physical infrastructure [but] hesitate – totally – when it’s time to ante up their fair share of financial support of our system.” Wrong. It’s not a lack of patriotism, and it’s not because these companies are trying to avoid paying what’s fair. As Heritage Foundation tax expert Curtis Dubay has pointed out, “they’ll continue paying the same amount of tax on their U.S. income if they invert. Rather, it’s to maintain their competitiveness with their foreign rivals in the growing global marketplace.” Seen in its true light, in fact, it would appear those who don’t want to level the playing field for their fellow Americans would appear to be acting in an unpatriotic fashion. So why are the president and others who criticize companies for inverting not taking the obvious steps – namely, reduce the corporate tax rate and stop taxing the foreign income of U.S. businesses? It’s the hallmark of a true leader to see a problem clearly and do everything possible to fix it. Why won’t the president and other foes of inversion follow Reagan’s example?

SocietyNews