Nowadays in polite society, we rarely hear anyone talk about strength of character, virtues or greatness. To discuss these matters would require making “value judgments,” and we are told we cannot judge. Openness is the only virtue we recognize.

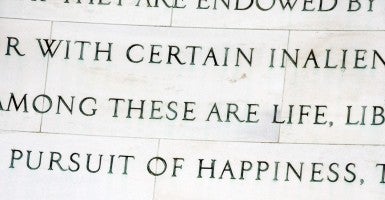

Our Founders thought differently. They recognized the republic they established could be sustained only if the people possessed certain virtues. Our Declaration of Independence, which we today commemorate, offers the signers themselves as an example of these virtues.

The spirit of the document is revealing. Unlike other similar documents that intend to stop at nothing to usher in a new order, our Declaration offers a calm, rational articulation of the principles justifying American independence. The Founders’ new order was to be restrained by rational laws and limited to the goal of securing rights in a government based on consent.

Neither do readers of the Declaration find the kind of fanaticism or childlike enthusiasm that passes for political rhetoric today—no utopian promises that “Yes, we can repair this world.” Prudent deliberation secures the “safety and happiness of the people;” it does not echo Michael Jackson. Prudence also requires the subordination of the passions that distort reason. Nothing in their writing smacks of our contemporary clichés claiming that being “passionate” about something, anything, is the goal of life.

Furthermore, the signers thought a jealous regard for rights, coupled with the strength to ensure they are not encroached upon—that is, “opposing with manly firmness [tyrannical] invasion on the rights of the people”—are virtues necessary to sustain a free people. But strength is incomplete without the willingness to sacrifice: Their vow to stake their “lives,” “fortunes” and “sacred honor” shows devotion to a common American destiny for which they were willing to give all.

In fact, several signers were captured by the British and tortured. Others lost children, and many lost their fortunes in the Revolution. The Founders were not hostage to petty ambitions or high-minded ramblings hiding selfishness—they vowed to make very real sacrifices, and they did.

In contemporary America, progressives have attempted to rid Americans of their intellectual firmness. They contend Americans might benefit from becoming passive beings, ruled together, uniformly, as an indeterminate mass by expert bureaucrats.

When Americans resist this form of rule, those such as former Energy Secretary Steven Chu explain, “The American public…just like your teenaged kids, aren’t acting in a way that they should act.” Is the American public merely a rebellious teenager, lacking the intellect to discern its own interests? Should the free people of America be reprimanded and held in contempt?

What Chu implies is that institutions and bureaucracies alone can rule citizens—and that “manly firmness” and independent, rational deliberation stand in the way. The Tea Party movement gives some hope and proof that American firmness still lives on.

The Declaration is an image of the peak of the democratic character: rational argumentation on the basis of one’s own intellect, patient equanimity devoid of hatred or resentment, “firm manliness” in the face of usurpation and prudent reflection on the ends of government. The Declaration perhaps comes closest to American poetry in its presentation of human possibilities.