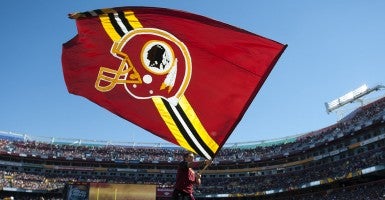

Today, the U.S. Patent and Trade Office’s Trademark Trial and Appeal Board, by a vote of 2 to 1, canceled the registration of six trademarks held by the Washington Redskins football team on the grounds that the word “Redskins” is disparaging to Native Americans.

There’s been increasing public scrutiny of the Washington Redskins’ name—with President Obama and many members of the Senate calling for the team to change its name. The legal issue before the Trademark Board, however, was not whether the term “Redskins” is viewed as disparaging by Native Americans today, but rather whether it was viewed as such by a “substantial composite” of Native Americans at the time the six Redskins trademarks were issued, from 1967 to 1990.

This is not the first time the Trademark Board has ruled against the Redskins.

In a case that begin in 1992, the board ordered the cancellation of the same trademark registrations, but a federal district court reversed that order finding that the board’s finding of “disparagement” was “not supported by substantial evidence” and the claims were barred by laches (a legal doctrine meaning the petitioners had waited too long to file their claim). The U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit agreed that the claim was time-barred, but did not opine on the district court’s ruling on the merits of the disparagement issue.

In 2006, a new group of five Native Americans filed a second petition to cancel the same trademark registrations and a majority of the Trademark Board ruled in the group’s favor. The majority concluded that the trademarks should be canceled because, in their view, the evidence supported the claim that the term “Redskins” was disparaging to Native Americans and brought them into contempt or disrepute at the time the trademarks were issued. The majority also rejected the defense of laches because of the “broader public interest” that they believe exists.

As the dissenting board member pointed out, however, the petitioners engaged in what “can most charitably be characterized as a database dump” resubmitting “most of the same evidence that the [original] petitioners submitted—evidence which the district court previously ruled was insufficient to support an order to cancel the challenged registrations as disparaging.” The dissenting board member further noted:

It is astounding that the petitioners did not submit any evidence regarding the Native American population during the relevant time frame, nor did they introduce any evidence or argument as to what comprises a substantial composite of that population thereby leaving it to the majority [of the Board] to make petitioners’ case have some semblance of meaning.

The evidence the board relied upon is anecdotal. None of the linguistics expert witnesses the board relied upon “specifically researched the Native American viewpoint of the word “redskin(s)” as it related to the football team. Further, the board referenced dictionary entries from the 1960s and electronic databases from major newspapers and magazines for the 1970s-1980s to determine how the term was used and whether it was considered offensive. But again, neither the dictionaries nor the databases shows how Native Americans viewed the term during the relevant time frame.

This cancellation will almost certainly be appealed and, given the precedents, stands a good chance of being reversed again. And at least one noted legal scholar has pointed out potential First Amendment issues raised by this decision.

It’s important to note the consequences of this ruling. The board has no authority to stop the team from using its name. Yet this cancellation means that the team will be severely hindered in preventing others from selling merchandise or services that use the term “Washington Redskins,” thereby depriving the business of a valuable property right. Team owner Dan Snyder has fervently defended the team’s name and has vowed “We’ll never change the name. It’s that simple. NEVER—you can use caps.” However, since NFL teams pool their merchandising revenue and divide it equally, the other owners may bring some pressure to bear on Snyder to change the name should he lose on appeal.

At the risk of being labeled (gasp!) politically incorrect, it is clear that the political correctness crowd is on the war path. Other teams, such as the Cleveland Indians, Atlanta Braves, Kansas City Chiefs, and the “Fighting Irish” of Notre Dame, may want to call their lawyers.