Who should manage teacher preparation programs at universities? According to the Department of Education, the right person for the job is U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan. Politico reported Friday that the Obama administration plans to provide millions in federal funding to reward teacher training programs that demonstrably impact student test scores:

The teacher training industry is already moving toward higher standards: Beginning in 2016, all institutions must meet new guidelines laid out by the Council for Accreditation of Educator Preparation. The accreditation process will require teacher prep programs to gather information on how their graduates affect student achievement, whether principals are satisfied with their performance and whether the newly minted teachers feel prepared when they enter the classroom, among other metrics. The regulations sketched out by Duncan would cover much of the same ground, but would go further by withholding federal aid from those institutions that fail to measure up.

The proposal is problematic for two reasons: 1) it is at odds with what we know about the effectiveness of paper credentials conferred by colleges of education, and 2) it’s not a job for the secretary of education.

What we know about paper credentials is that they are a poor indicator of future teacher performance. “The current system, which focuses on credentials at the time of hire and grants tenure as a matter of course, is at odds with decades of evidence on teacher effectiveness,” argue economists Douglas O. Staiger and Jonah E. Rockoff in the Journal of Economic Perspectives.

Moreover, “…some programs may appear stronger not because they provider better opportunities for students to learn to teach but because they are able to attract better teacher candidates,” caution scholars Donald J. Boyd, Pamela L. Grossman, Hamilton Lankford, Susanna Loeb and James Wyckoff in the Journal Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. It is important to control for teachers’ entering characteristics when making determinations about the effectiveness of a particular teacher preparation program. For instance, if one program is attracting candidates with high GPAs and another program is not, it is possibly the first programs’ students—not the education they receive in the program—that leads to that program producing better teachers than the second program does.

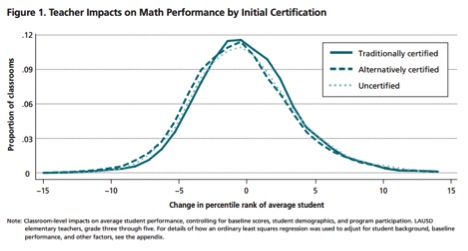

Research from the Brookings Institution has demonstrated that there is no correlation on teacher impacts on student math performance and initial teacher certification. “To put it simply, teachers vary considerably in the extent to which they promote student learning, but whether a teacher is certi?ed or not is largely irrelevant to predicting his or her effectiveness.”

In other words, paper credentials cannot predict how effective a teacher will be.

While the roughly $180 billion in annual federal student aid for colleges has mingled the federal government with higher education policy, improving the teacher workforce requires state and local-level policy changes. States and local school districts should remove many of the barriers to entering the classroom—namely requirements for certification—but should demand excellent performance of teachers (as measured in part by student growth on assessments) once a teacher enters the classroom.

Enabling aspiring teachers and mid-career professionals an easier route to the classroom— but rigorously measuring teacher performance once hired—holds far more promise for improving the teacher workforce than throwing additional federal funding at schools of education.