We’ll be updating this blog throughout the afternoon and night as Heritage experts examine the farm bill, so please keep refreshing for updates. — Katrina Trinko

Another Unrelated Program Added to the Farm Bill

The logrolling only has gotten worse with the new farm bill. The farm bill includes the Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) program.

A Department of Interior (not Agriculture) program called Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) provides compensation to local governments to help make up for lost revenue resulting from federal land ownership (federal land generally can’t be taxed).

This program was left out of the recent omnibus spending bill, but now has been added to the farm bill. This program is particularly important to western legislators because of the vast federal land ownership in the west.

Food stamps and farm programs are combined together to get the farm bill passed. Now another unrelated program has been included in the bill, and will certainly act as a carrot for some western legislators to vote for the farm bill. (Section 12312).

— Daren Bakst

Congress Fails to Create a Real Work Requirement for Food Stamps

A strong work requirement is the most important reform for food stamps, yet policymakers failed to deliver. Instead, Congress opted for a mere work “suggestion.”

Without a work requirement it is difficult to ensure food stamps are not going to those who could otherwise work. A work requirement acts as a gatekeeper: those who really need assistance can still get it, while those who may not really need it will be deterred, thus targeting resources to the truly needy. It also encourages individuals to move towards work, and it can provide job training and other employment help.

It was a work requirement that was at the heart of the successful 1996 welfare reform, which changed the then Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program to the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program. After its enactment, welfare rolls declined by half, unemployment rates among low-income individuals decreased, and child poverty dropped substantially. Like the 1996 reform, food stamps should be reformed to require able-bodied adults to work, prepare for work, or at least look for work in exchange for receiving food stamps.

Between FY 2007 and FY 2010, the number of able-bodied adults without dependents on food stamps skyrocketed, more than doubling from roughly 1.7 million to 3.9 million. While the total number of food stamp participants also grew substantially–by 53 percent–the rate of growth for able-bodied adults without dependents was about 127 percent.

Self-sufficiency for able-bodied adults should be the goal of any sound welfare policy. Unfortunately Congress has once again failed to address the importance of work.

— Rachel Sheffield

Gut the Energy Programs in the Farm Bill

Assistance. Isn’t that just a fancy word for taxpayer-funded handout? In the most current version of the farm bill (as well as past versions), it sure is. The legislation includes direct handouts and loan guarantees for advanced biofuels and bio-refineries, and bio-based product manufacturers. It also re-authorizes the Rural Energy for America Program, where your taxpayer dollars help “complete energy audits and feasibility studies, complete energy efficiency improvements, install renewable energy systems. We have programs that help convert older heating sources to cleaner technologies, produce advanced biofuels, install flexible fuel pumps, install solar panels, build biorefineries, and much more.” The farm bill even includes the re-authorization of the biodiesel fuel education program to help government entities, vehicle fleet owners and the public about the benefits of biodiesel use.

You know who else can do all those things if they make economic sense? The private sector. If these efficiency improvement, renewable energy installation or increased biodiesel use for transportation make sense, private companies can pay for, develop and sell the production without the “assistance” of the taxpayer. The energy programs in the farm bill are nothing more wasteful green subsidies and Congress should eliminate them, not reauthorize them.

— Nicolas Loris

Policy to Continue to Allow Those with Big Bank Accounts to Get Food Stamps

The farm bill will allow “broad-based categorical eligibility” to continue, a policy that allows states to bypass asset tests for food stamp recipients. This means that individuals could have an unlimited amount of assets and still be eligible for food stamps as long as their income is low enough.

The House voted to end broad-based categorical eligibility. The Senate bill turned a blind eye to it. After negotiations, the House has given way to let this problematic policy continue.

Particularly in times when resources are tight, welfare assistance should be targeted to those most in need. Ending broad-based categorical eligibility would help ensure that food stamps are directed to those who need them most, restoring the integrity of the food stamps program.

— Rachel Sheffield

Ends Loophole that Artificially Boosts Food Stamp Benefits

The farm bill would end the “Heat & Eat” loophole in food stamps. This is one small, positive step the farm bill takes to improve the food stamps program.

“Heat & Eat” is a loophole states have exploited that allows them to artificially boost the amount of a household’s food stamp benefit. Here’s how this works:

“The amount of food stamps a household receives is based on its ‘countable’ income—income minus certain deductions. Households that receive benefits from the Low-Income Heat and Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) are eligible for a larger utility deduction. In order to make households eligible for the higher deduction—and, thus, greater food stamp benefits—states distribute LIHEAP checks for amounts as small as $1 to food stamp recipients.”

The farm bill tightens this loophole by requiring households to receive more than $20 annually from LIHEAP before they can qualify for the higher utility deduction.

Congress is right to deal with this loophole. But it’s only a minor reform for a program in drastic need of change.

— Rachel Sheffield

The $6 Billion Last Second Surprise with the Farm Bill

The CBO score has just been released on the eve of the House farm bill vote. The farm bill savings are far less than what has been reported—and the reported savings of $23 billion over 10 years were miniscule as it is. Instead of $23 billion, the savings are only projected to be $16.5 billion over 10 years.

The House is about to vote on a farm bill tomorrow, even though they will have had less than 48 hours to review the text. Now, they will have less than 24 hours to process CBO’s projected savings in the bill.

This last-second chance to see the real projection should be shocking for any legislator concerned with the fiscal mess of this nation. This number itself should be unacceptable, and the process is indicative of the closed manner in how the farm bill has been shoved down the throats of Americans.

— Daren Bakst

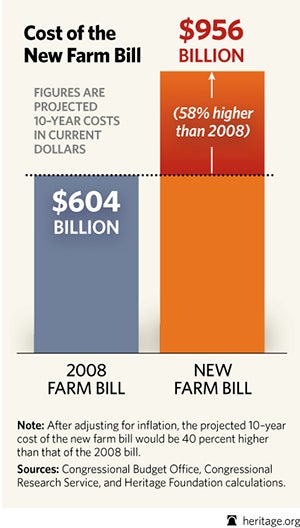

New Farm Bill’s Projected Spending is 58 Percent Greater Than 2008 Farm Bill

The Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) projected 10-year costs for the 2008 farm bill were $604 billion. Costs have skyrocketed. The projected costs for the new farm bill are $956 billion. Based on current dollars, this is 58 percent higher than the projected costs from the bill passed in 2008. Like with the 2008 bill, the costs will likely be far greater.

When adjusted for inflation, the projected costs are about 40 percent higher than the projected costs of the 2008 bill.

— Daren Bakst

Farm Bill: Taxpayers Hurt by Arguably Worst Negotiation in History

Taxpayers got slammed by the legislators working out the differences between the House and Senate farm bills in conference. Two bad bills went in, an even worse bill came out, especially when it comes to spending. The House voted for this new farm bill, and the Senate is expected to vote on the bill soon.

House Bill: The House passed a separate food stamp bill and a farm program bill, and then combined them together in one bill for conference. The total projected savings between the two would have been about $51.8 billion.

This includes spending reductions of $39 billion for the food stamp bill (H.R. 3102) and $12.8 billion for the agriculture-only (non-SNAP) farm bill (H.R. 2642).

Senate Bill: The projected spending reduction for the Senate farm bill (S. 954) was $17.8 billion.

New Farm Bill: The projected spending reduction is $16.5 billion.

The Senate was seeking a much smaller spending reduction than the House. Showing its “brilliant” negotiating skills, the House agreed to a spending reduction that is actually smaller than what the Senate sought.

This is like trying to sell a house for $200,000, receiving an offer for $190,000, and then demanding that the buyer pays you $185,000.

Senators interested in protecting taxpayers should have already been shocked at the tiny $17.8 billion reduction that was part of their bill. The smaller reduction in the new bill should be seen as out of hand.

This isn’t just a fiscal conservative issue—there are plenty of reasons why legislators regardless of ideology should be concerned about the spending. Not least of which is the fact that the new farm bill doesn’t make any effort to try and place some reasonable limits on forcing taxpayers to hand over their money to wealthy agribusinesses.

This is highlighted by the rejection of a minor Senate proposal that would have limited taxpayer subsidies to wealthy farmers. Taxpayers pay about 62 percent of the premiums for farmers purchasing crop insurance. That’s a sweet deal for farmers.

The Senate injected a little bit of common sense in the process by trying to reduce the premium subsidy level for farmers with an adjusted gross income of $750,000 or more. This minor reform was shot down, showing how extreme this new farm bill is when it comes to protecting special interests.

Taxpayers were ignored with this bill and the special interests are the big winner.

— Daren Bakst