Calls to spend more on teachers are likely to come up in tonight’s debate. More likely still, we’ll hear accusations that Governor Mitt Romney wants to slash education spending by 20 percent.

This figure is a reference to the House of Representatives-approved budget, authored by House Budget Committee chairman Paul Ryan, which aims to trim non-defense discretionary spending but does not specify cuts to K-12 education.

While the House-approved budget does not specify a 20 percent reduction in federal education spending, such a move would be wise. The American public education system has shown no improvement despite a near tripling of federal spending since the 1960s.

President Obama wants to aggressively increase the amount of money taxpayers spend on Washington education programs. Specifically, he has been trying to sell the notion that the federal government must spend more taxpayer dollars to fund education jobs and that failing to do so will result in fewer teachers in the nation’s public schools.

This campaign began in earnest with the so-called stimulus in 2009, which gifted a one-time bonus of nearly $100 billion to the Department of Education. The Administration states that “approximately 275,000 education jobs, such as teachers, principals, librarians, and counselors, were saved or created with this funding.”

On the heels of that historic infusion of cash, a year later, in 2010, the Administration pushed, and Congress passed, the Education Jobs Fund—a $10 billion public education bailout—in order to “save or create education jobs for the 2010-2011 school year.” Education Secretary Arne Duncan argued that the funding would “enable schools to keep an estimated 160,000 or more education jobs.”

And now, as part of his “Education Blueprint,” President Obama has put forward a breathtaking proposal to spend another $25 billion “to provide support for hundreds of thousands of education jobs.”

Aside from constitutional issues involving federal pay for education employees, spending billions of taxpayer dollars through Washington to prevent public school layoffs are unwise and unnecessary.

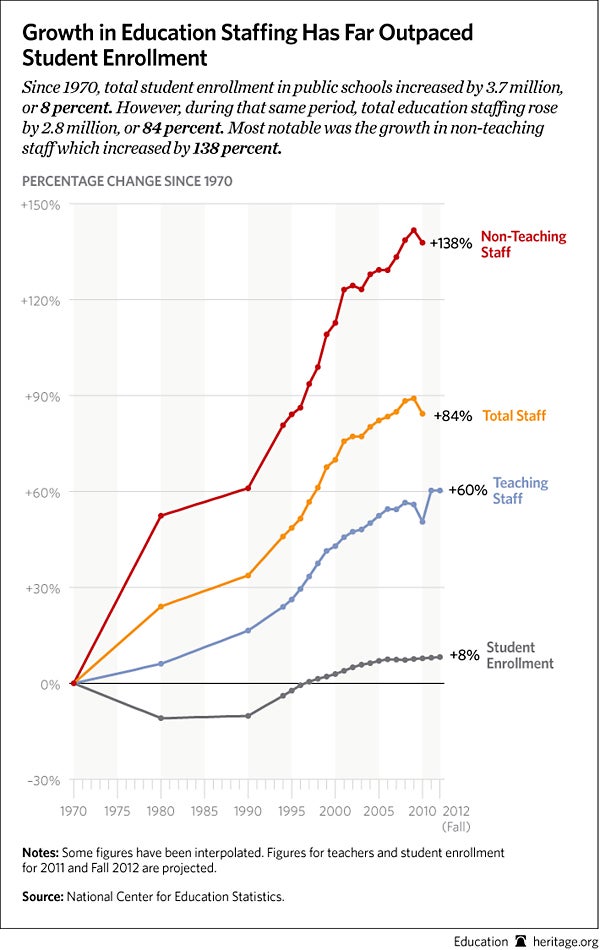

The White House often conflates education jobs with teaching positions, leaving the impression that reductions in staff rolls in the public education system will necessarily lead to fewer teachers in the classroom. While many school districts face potential staff reductions, the growth in non-teaching staff over the past five decades should inform decisions about education staffing and spending.

Teaching and non-teaching staff positions in public schools across the country have increased at far greater rates than student enrollment over the past four decades. From 1970 to 2010, student enrollment increased by a modest 7.8 percent, while the number of public-school teachers increased by 60 percent. During the same time, non-teaching staff positions increased by 138 percent, and total staffing grew by 84 percent. Teachers now comprise just half of all public education employees.

If school districts are cash poor, they should trim non-teaching staff positions—there is ample room. Removing federal red tape would help in such an effort, as a non-trivial number of administrative positions are the result of the bureaucratic compliance burden associated with the operation of federal education programs.