‘War Is My Life’: A Journey Along the Front Lines in Ukraine

Nolan Peterson /

SHCHASTYA, Ukraine—The late winter weather in Ukraine alternates among frigid, cool, snow, and rain—teasing the arrival of spring.

The 2-year-old war, which has ravaged eastern Ukraine, killing more than 10,000 and displacing more than 1 million, is as fickle as the weather—teasing the possibility of peace without ever achieving it.

Both sides of the conflict renewed their commitment to the cease-fire in September, reducing the scale and intensity of the Ukraine war to a shadow of what it was during the fall of 2014 and the first few months of 2015.

But the war is not over.

Ukrainian troops patrol no man’s land outside the town of Shchastya. (Photos: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

During a six-day period from Feb. 27 to March 3, this correspondent visited Ukrainian troops deployed at both the front line and the rear echelon, stretching from the southernmost extension of the front lines outside the city of Mariupol to the war’s northern limit near the town of Shchastya, outside the separatist-controlled city of Luhansk.

Along the front lines, Ukrainian troops are dug in and ready for combat.

As one soldier put it: “This is my life now.”

Combined Russian-separatist artillery, tank, mortar, and small arms attacks occur daily at hot spots near Donetsk, capital of the Donetsk People’s Republic, one of two breakaway territories.

“It’s like this every day,” John Slobodyan, 23, a soldier in the Ukrainian army’s 93rd Brigade, said. He spoke as the bass notes of artillery cut through the air at a Ukrainian outpost near the town of Karlivka, about six miles from Donetsk.

“There is no cease-fire,” Slobodyan said.

The seaside town of Shyrokyne, just outside Mariupol on the Sea of Azov, marks the southern terminus of the front lines. After a trench and artillery battle that began in February 2015, Ukrainian forces seized control of the town last July.

Shyrokyne now lies in ruins, and there are no civilians left living there. The town remains off limits as Ukrainian units demine the area and remove booby traps retreating combined Russian-separatist forces left behind.

Two hundred miles from Shyrokyne at the northern limit of the front lines around Luhansk, capital of the Luhansk People’s Republic, the war has become a back-and-forth of sniper potshots. Ukrainian patrols also search for combined Russian-separatist units, which slip across the lines to set up ambushes and plant improvised explosive devices, in a daily cat-and-mouse game.

“Is this a war or not? It is uncertain,” Andriy, 30, a soldier in the 92nd Brigade, said, on the front lines near Luhansk.

Frozen Conflict

The sounds of artillery, mortars, and small arms cut through the cool breeze on a sunny day at a Ukrainian army outpost near the town of Karlivka.

A group of Ukrainian soldiers from the 93rd Brigade stood outside a wood cabin, talking, joking, and smoking cigarettes. The pace of the nearby artillery increased, catching the soldiers’ attention.

One by one, they looked across a small lake toward rolling hills still brown from the winter, behind which emanated the sounds of war.

But the soldiers remained relaxed. Some played with a litter of puppies the unit had adopted. One soldier chopped up a pig leg in preparation for a barbecue dinner (called shashlik in Ukraine).

The soldiers’ laid-back demeanor highlighted the banality of the moment.

With the sounds of artillery in the background, Ukrainian soldiers in Karlivka appear relaxed and at ease.

The soldiers said combined Russian-separatist forces attack Ukrainian positions in the area every day. They said the attacks usually comprise 120 mm and 82 mm mortars, small arms, and sniper fire, although larger caliber artillery and Grad rockets sometimes are used. They also said tanks routinely fire at their positions in the town of Pisky, just outside the Donetsk airport.

The 93rd Brigade has been deployed to the war for about a year and a half. Many troops are desensitized to the violence and treat the audible evidence of nearby battles flippantly. They remember when the fighting was more intense, and despite the daily attacks, the soldiers consider things relatively tranquil.

“It comes and goes,” said Rostislav Bryl, 37, a soldier in the 93rd Brigade. “It’s normal to hear the artillery. But compared to what it was before, it’s a lot less.”

The diminished pace of combat since September has not inspired hopes for a lasting peace. Many soldiers expressed concern about a potential “Yugoslavia” scenario and feared years of protracted skirmishes.

“We’ve already been here for a year and half,” Bryl said. “We’re tired and ready to go home.”

Other soldiers, however, seemed more concerned with the cease-fire’s rules of engagement than the idea of returning home.

“It can get boring,” said Bogdan Kapusta, 34, a soldier in the 93rd Brigade. “We want to go to the front lines to fight.”

Regular troops and commanders expressed frustration with the rules of the Minsk II cease-fire, which first went into effect in February 2015. In Karlivka, Ukrainian troops said they are allowed to use machine guns to retaliate only after artillery and mortar attacks.

“Yeah, we’re frustrated,” Bryl said. “When you’re being shot at with artillery and you can only shoot back with machine guns, it’s really frustrating.”

Divided Loyalties

Many villages along the front lines are battle-scarred; some have become ghost towns. The territory on the fringes of the front lines is a land in purgatory, where normal life is as frozen as the conflict itself.

This correspondent saw civilian vehicles lined up at ramshackle military checkpoints, where soldiers check IDs and pop trunks, looking for smuggled weapons and contraband. Street vendors sold snacks and military uniforms from stands set up in front of tank barriers and trenches. Children rode bicycles on roads flanked by minefields.

In many of these towns, Ukrainian soldiers in uniform have become a regular fixture on the sidewalks and in cafés and restaurants. They sometimes earn a long look from a civilian, but their presence is mostly treated with indifference. The military’s presence has become an unexceptional part of the daily tableau in towns along the front lines.

After a month of skirmishes, Ukrainian forces retook the town of Popasna in the Luhansk region in July 2014.

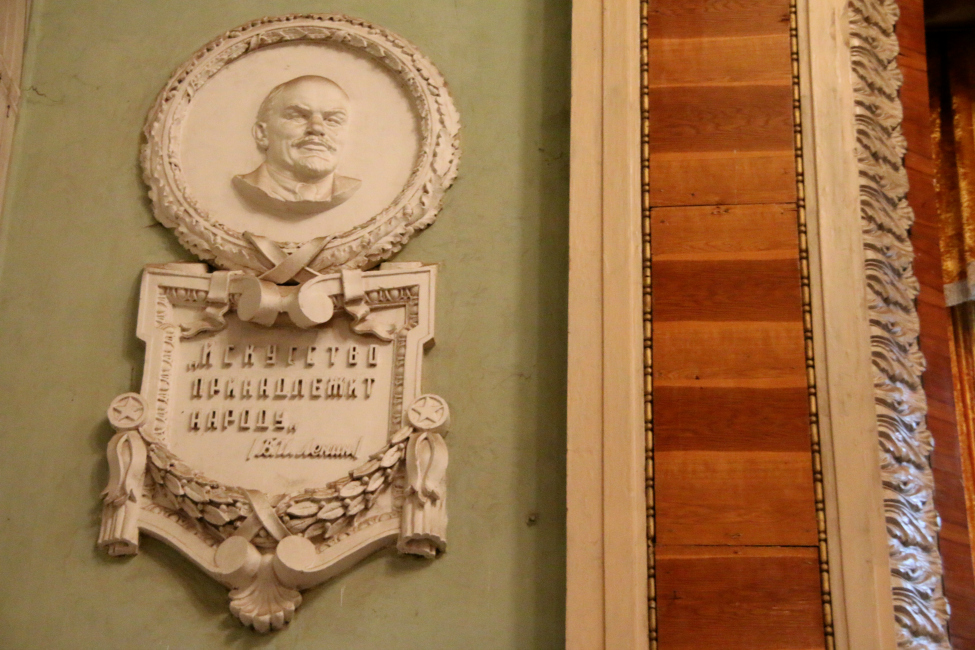

A year and a half later, Ukrainian soldiers garrisoned in the area met in Popasna’s Soviet-era culture hall to rehearse for an International Women’s Day variety show set for March 8. The soldiers spent the evening performing traditional Ukrainian songs in the theater, where busts of Vladimir Lenin and Karl Marx are still hung on the walls.

In some areas along the front lines, loyalties remain quietly divided between those who support the Ukrainian government in Kyiv and those who favor the pro-Russian separatists.

A street cleaner in Mariupol, an older woman, harangued a group of Ukrainian volunteers and combat veterans, one of whom was in uniform, for speaking in Ukrainian—the national language.

“You’re in a Russian-speaking area, you should show respect and speak Russian,” she insisted.

Sitting Idle

The outskirts of towns abutting the front lines have become militarized frontiers.

A network of military trenches rings the Ukrainian-controlled town of Shchastya (which translates to “happiness”), about nine miles north of Luhansk. The town is a key possession for Ukraine due to its power plant, which supplies electricity to the region.

The Ukrainian trenches outside Shchastya are reminiscent of photographs of World War I. The sides of the labyrinthine trenches are lined with cut timber, and the floor is bare earth. Ammunition boxes are ubiquitous.

Soldiers live in hardened dugouts replete with electricity, heat, TVs, and Internet. Rows of bunk beds constructed from felled trees fill the interiors. Clothing, military equipment, souvenirs from home, and foodstuffs consume empty space.

A furnace heats the room to an uncomfortable temperature, and many soldiers lie in bed stripped to their underwear to deal with the heat. Outside, the earth is a muddy morass, the result of melting snow and intermittent rains.

The temperature quickly drops after sunset, and soldiers on watch are bundled up in thick coats and beanies. The military now provides cold-weather gear, the soldiers said, unlike the early days of the war, when troops relied on civilian volunteers for almost everything, including uniforms, food, and water.

The soldiers said the military supply chain has improved, but civilian volunteers still meet food and water shortfalls, and uniforms remain a hodgepodge from different countries. With no common uniform, soldiers attach colored tape to their helmets and body armor to distinguish themselves from their enemies.

At night, soldiers on watch in a blacked out observation post took turns peering through a single night-vision scope to scan separatist positions across 1,200 meters of no man’s land. A red light dimly illuminated a map of the area. The soldiers clustered around a small furnace to keep warm in between shifts at the scope.

Night-vision technology is still scarce within Ukrainian ranks, largely limiting combat to daylight hours. Lack of encrypted communications is another challenge. Ukrainian soldiers often communicate with off-the-shelf Motorola walkie-talkies, sharing frequencies with their enemies. The two sides sometime taunt each other over the open airwaves.

Machine gun nests are positioned along the Ukrainian lines, and troops claim that in the event of an attack they can fire the guns within 10 seconds. But commanders feel defenseless in the event of a combined Russian-separatist offensive.

According to troops in the field, Ukrainian forces have pulled back all heavy weapons from the front lines under the terms of the February 2015 cease-fire called Minsk II.

“We are very nervous without a way to defend ourselves,” 2nd Lt. Yuri Bandarenko, 22, a company commander in the 92nd Brigade, said.

“We’re just simple soldiers with only small arms to defend ourselves,” he added.

Bandarenko said there had not been an artillery attack on his position in months, but small arms gunfights in the area, and drone overflights were common.

Bandarenko’s unit has been deployed to the war for one year and four months. He said the downturn in intensity has left his soldiers restless and frustrated. As a commander, he said, he aims to maintain both the morale and the combat readiness of his troops:

Half the men are replacements and have not been in combat, and they don’t know how to react to the artillery. And the half who have been in combat have been sitting idle for so long they’ve forgotten what to do.

It’s not good for morale when an army doesn’t fight. The bureaucracy takes over, and the soldiers are tired of it.

No Man’s Land

Most Ukrainian army units include a subset of crack troops somewhat equivalent to a special operations team in the U.S. military. These troops are usually in their 30s and 40s and better trained. They conduct the majority of combat patrols.

One such group of elite troops, an intelligence unit from the Ukrainian army’s 92nd Brigade, escorted this correspondent along the front lines and into no man’s land from a front line position called “Granite,” near Shchastya.

These specialized troops regularly patrol through no man’s land around Luhansk, frequently making contact with their enemy. Consequently, they are on constant alert and take the war deadly seriously.

Approaching the front, the intelligence unit soldiers kitted up in body armor and drew weapons. Vehicles never travel alone, the soldiers said. On this day, a pickup truck carrying six troops, a machine gun mounted in the back bed, escorted an SUV carrying two soldiers, a civilian volunteer, and this correspondent.

Andriy, the driver of the SUV, has been deployed to the war for two years. He pulled a green balaclava down over his face, drew his pistol, and held it in his steering hand as he navigated across the dirt roads.

“We have to be ready for anything,” Andriy said. “There is shooting going on pretty much every day.”

Soldiers from an intelligence unit in the 93rd Brigade draw weapons in anticipation of ambushes as they drive into no man’s land.

At the Granite outpost, Ukrainian troops live in trenches and fortified bunkers. They are dug in and on edge.

Past Granite, about three miles of no man’s land separates Ukrainian and combined Russian-separatist positions. Andriy called it the “gray zone.”

“We can’t control this area,” he said. “We only patrol through it.”

As they dismounted from their vehicles at a crossroads, the intelligence unit soldiers set up a defensive perimeter and deployed a sniper to watch over the scene. Two soldiers identified a location hidden in the nearby trees where a separatist unit ambushed and killed six Ukrainian civilian volunteers passing by the crossroads last summer.

Driving across no man’s land, soldiers pointed out the locations of past separatist ambushes. They stopped to observe several burned out swaths of the roadside, littered with twisted pieces of metal, where separatist explosive devices had detonated.

The soldiers identified places where they had fought and captured enemy patrols—including the location of a firefight with a Russian reconnaissance unit in May 2015 in which Ukrainian troops captured two Russian Spetsnaz GRU soldiers. Three Ukrainian soldiers died in that battle.

Soldiers in the intelligence unit expressed frustration with what they claimed to be the inaccurate portrayal of the conflict in both Ukrainian and international news. They said most media outlets ignored the reality of conditions on the ground, downplaying the continued violence as well as Russia’s hand in the war.

A meeting in Paris on March 3 among the foreign ministers of France, Germany, Russia, and Ukraine—the “Normandy Four”—produced no new progress on charting a political solution to the conflict in Ukraine. Negotiations stalled on several key points, including conditions for the full withdrawal of weapons from the front lines, the return of prisoners, and how elections in the breakaway territories should be run.

The 92nd Brigade soldiers asked questions about the latest developments in the Normandy Four negotiations. Apart from the reduction in fighting since September, they see little concrete evidence on the front lines of the myriad deals hashed out by Ukrainian, Russian, and European leaders in faraway capitals.

“Everybody is frustrated when they shoot at you and you can’t shoot back,” Andriy said, discussing the rules of engagement under the Minsk II cease-fire. “But if there is an order to free the occupied territories, we are ready.”

‘War Is My Life’

Apprehension about returning to civilian life was a common thread among soldiers up and down the front lines and at rear positions, where soldiers rest between rotations at the front.

A unit of Ukrainian marines deployed to Mariupol primarily comprised draftees and reflected a cross section of Ukrainian society. The marines ranged in age from 21 to 56 years old. The list of their previous professions was eclectic, including engineers, factory workers, lawyers, and two cemetery groundskeepers.

In July 2015, the troops took over the defense of nearby Shyrokyne from various Ukrainian volunteer battalions, which had been fighting for the town since February.

Marines have been deployed to the Mariupol area for more than one year and are scheduled to rotate home soon. Many were excited about their homecoming, but a few also were nervous about returning to civilian life and their families after the life-altering experience of combat.

Among troops who have volunteered to go to war, however, there was a markedly different attitude about going home than among draftees. Within regular Ukrainian units such as the 93rd and 92nd Brigades (which comprise a mix of volunteers and draftees), as well as within all-volunteer units such as Right Sector, many volunteer soldiers pledged to keep fighting until the war is over.

“I will stay in until the very end,” Andriy, a volunteer who has a wife and child in his hometown of Kharkiv, said. “But my wife is very worried.”

“The spirit depends on the person,” Igor Khlodylo, a Ukrainian National Guard tactical medic stationed outside Popasna, said.

“Some are eager to fight, and some are just here to do their service,” he said.

Right Sector soldiers share their wartime experiences with a team of civilian volunteer psychologists.

Right Sector is a Ukrainian volunteer battalion, one of the ad hoc civilian fighting units born of the 2014 Maidan revolution. These paramilitary groups bolstered the under-equipped and outmatched regular Ukrainian military in the opening months of the war.

At a Right Sector base at a former Soviet-era children’s camp hidden in a forest near Dnipropetrovsk, a group of soldiers gathered for a dinner of varenyky (dumplings), borscht (beetroot soup) and salo (salted pig fat).

The base, a few hours’ drive from the war zone, is a training facility as well as a staging area for troops in between two- to four-week rotations on the front line.

After dinner, about 40 soldiers pulled up chairs to listen to a team of civilian volunteer psychologists who discussed the challenges of returning to civilian life and the symptoms of post-traumatic stress.

“I feel more at home in the war than when I go back home,” one soldier, 41, told a psychologist. “I need rehabilitation … my wife needs your help.”

“I don’t want to go back to civilian life,” a 36-year-old soldier said.

Heads nodded among the other soldiers as he added:

“I don’t know what I’ll do when the war is actually over. I can’t imagine it. This is my life now. War is my life.”