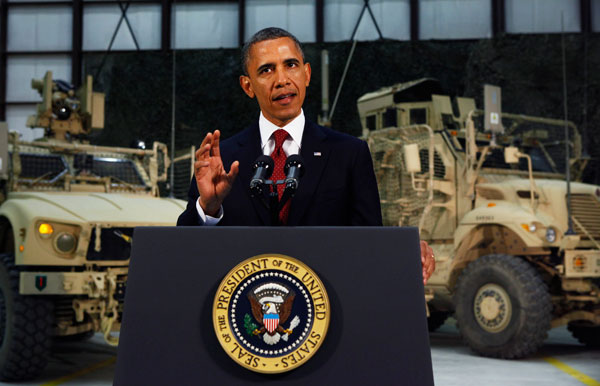

President Barack Obama delivers an address to the American people on US policy and the war in Afghanistan during his visit to Bagram Air Base (AFP PHOTO / POOL / Kevin LAMARQUEKEVIN LAMARQUE/AFP/GettyImages)

This week, the President marked the death of Osama bin Laden with a self-congratulatory campaign ad. If Lincoln had spent the entire Gettysburg Address talking about himself, it wouldn’t have been quite that crass. Now, the President zips to Afghanistan—coincidentally on the anniversary of the Seal Team Six raid.

House Armed Services Chairman Buck McKeon (R–CA) wryly noted that the visit came “[a]fter nearly a year of not speaking about the war and 17 months of not visiting the war zone.”

Obama’s remarks from “an undisclosed location” at Bagram Air Base included a few zingers that leave one wondering if all the speechwriters have left to join the campaign staff.

The biggest “I can’t believe he said that” moment had to be “We can see the light of a new day on the horizon.” Okay, so at least he didn’t declare it was “a light at the end of the tunnel.” Different metaphor—but it still had that used car salesman feel.

What the President did not discuss is how he has made a muddle of the counterinsurgency strategy in Afghanistan since day one. After dawdling for months before making his “decisive” decision, Obama promptly gave the commanders on the ground about half the troops they requested, and he gave them about half the time they said they needed before he started drawing down the troops. In his speech tonight, the President declared that the U.S. needs “a clear timeline to wind down the war.” Coincidentally, like his surprise trip to Kabul, the timeline just happened to fit with his reelection campaign.

The President’s object lesson in self-congratulatory speechwriting obscured the only real ray of light in his dismal Afghan policy: the signing of the Strategic Partnership Agreement (SPA). As Heritage regional expert Lisa Curtis wrote, “[t]he agreement will both demonstrate to the Afghans that the U.S. will remain committed to the country long after 2014 and provide a framework for the U.S. to maintain a residual presence to train Afghan forces and conduct counterterrorism missions.” In other words, while the President has put all the success in Afghanistan in jeopardy by hastily heading for the exit, there is a framework that would allow the U.S. to go back in and fix it—so we don’t just wind up back where we started on September 10, 2001.

Curtis notes:

Concluding the SPA demonstrates the U.S. will not abandon Afghanistan like it did in 1989. It also spells out an important U.S. red line to the Taliban, who have long called for expelling all foreign forces from the country. The Taliban criticized the Afghan government for moving forward with the SPA, saying the U.S. goal was to prevent the institution of a true Islamic government and to establish an army hostile to Islam that protects Western interests in the region.

Curtis concludes her analysis on a cautionary note. “The question is whether the Taliban would agree to restart talks with the U.S. in light of the agreement,” she points out. “From the U.S. perspective, talks with the Taliban are desirable only if they result in ensuring that Afghanistan will never again become a base for international terrorists.”

For now, the U.S. is better off focusing its resources on supporting anti-Taliban elements that share U.S. goals in the region. The President should spend a lot more time focusing on that goal than worrying about how Afghanistan plays in his reelection.

And he should get better speechwriters.